I Came to Ruin You: The Collecting Practices of K-Pop Fandoms

From photo cards to video art installations, a tour through a recent exhibition showcasing K-pop fans’ communal creativity and cross-cultural exchanges.

by Rea McNamara and Bo Shin

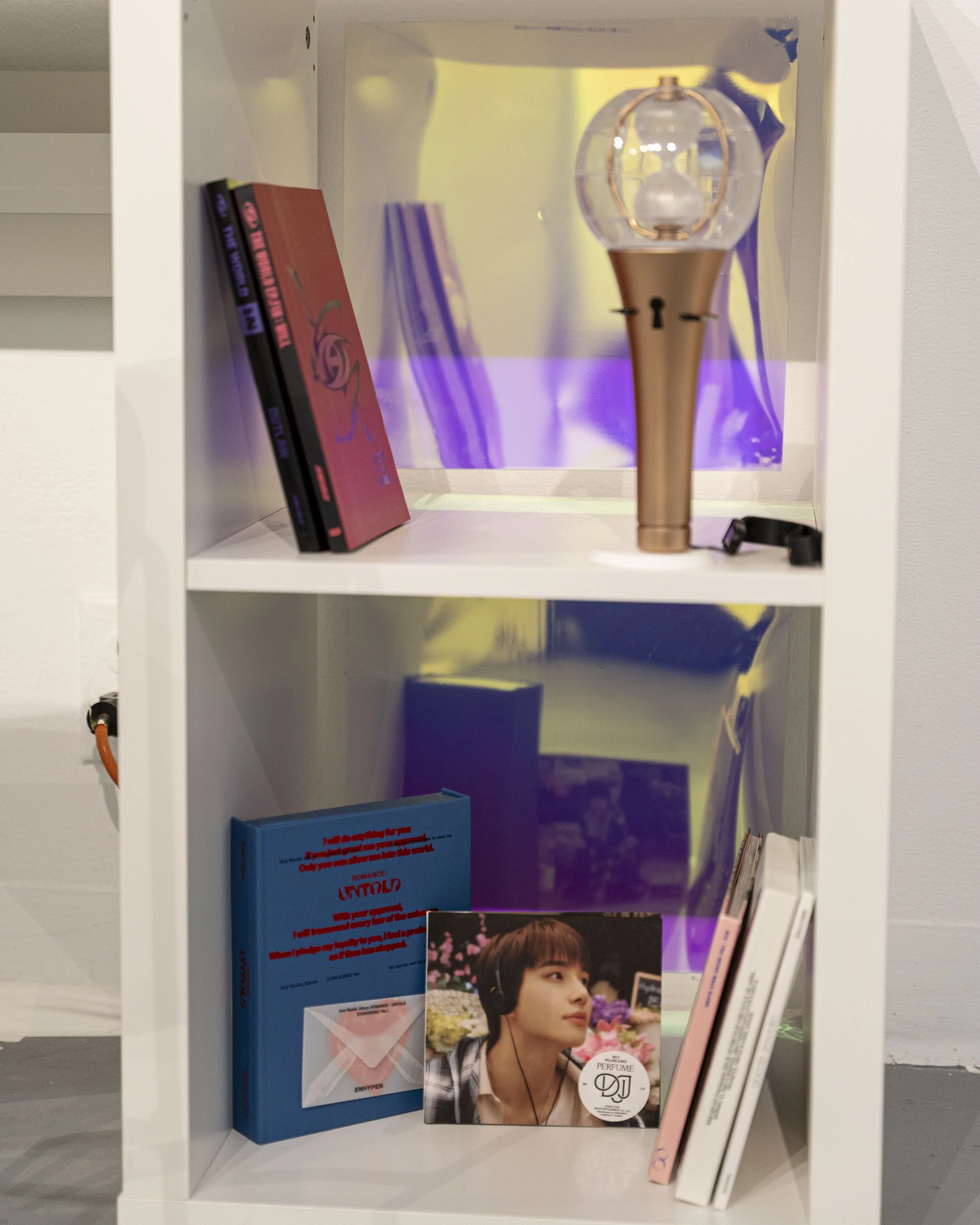

Installation view featuring Lux Pyre art installation and Sin Tung Ng (Steffi)’s IU fan collection from I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms (2025) at York University’s Special Projects Gallery. All exhibition documentation featured in this article was taken by Ana Figo (@ana_figo on IG).

This month’s Fansplaining piece is a bit of a departure from our usual fandom reporting and critical analysis: for the first time, we’re excited to share a virtual art exhibit of sorts, from Toronto-based curators and BTS fans Rea McNamara and Bo Shin. I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms was on display at York University this past spring, and what follows is an expanded version of the exhibition’s brochure, plus images, videos, and interviews with some of the fan collectors and participating artists Jiwon Choi and Lux Pyre.

As always, we were able to publish this piece because of the continued support of Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more fandom writing in the future, please consider becoming a monthly patron or making a one-off donation!

In the 2017 song “Pied Piper,” the K-pop group BTS uses the infamous folktale as a cautionary metaphor for the band’s relationship with their fans’ all-consuming habits. The song begins in Korean with a verse by rapper and group leader RM cataloging the content fans devour—videos, photos, Twitter. The band’s vocal line (members Jin, Jimin, V, and Jungkook) then sultrily harmonize in the chorus about how fans need to “follow the sound of the pipes,” as described in a translation by the authoritative BTS translator Doolset.

While Jimin sings about being dangerous and sweet in Korean, main vocalist Jung Kook soon cuts in: “I came to rescue you; I came to ruin you” before closing in English, “I’m takin’ over you.” Like the original Pied Piper of Hamelin, K-pop idols lure fans into their dazzling orbit with translanguage and affective bodily expressions: to follow the song of heightened visuals, diverse sounds, and complex choreographies. This, in turn, leads K-pop fans to be in a community with other fans across fandoms and musical genres, who navigate within a local and global ecosystem of transcultural consumer practice.

Taking inspiration from one of the few K-pop songs about stan culture, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms explores K-pop fandoms as cross-cultural sites of exchange and knowledge mobilization. The research-based curatorial project combined collected K-pop fan memorabilia alongside artworks engaging with K-pop fandom as a subculture with a broad range of artistic and community-based practices.

Installation view: Collection of Bo Shin (co-curator) from I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025.

Select BT21 memorabilia (LINE and BTS collaboration character goods), H.O.T.'s second album (1997), and BTS’s PROOF album (2022).

Full disclosure: We, as co-curators, have a K-pop fandom in common. We are “ARMY,” the eponymous fandom of BTS. Originally an acronym for “Adorable Representative M.C. for Youth” (harkening back to BTS’s roots as a hip-hop idol group), over the past decade, ARMY has become one of the most consequential global fandoms in recent memory.

With this fan-curator positionality, we built upon a burgeoning body of work by artists, curators, and art historians who adopt fandom as an expanded curatorial methodology. This included an exhibition-making case study written by another ARMY curator and writer, Sophia Cai, in the reader Bangtan Remixed (Duke University Press, 2024). More broadly, Fandom as Methodology (Goldsmiths Press, 2019), an anthology co-edited by art historians Catherine Grant and Kate Random Love, explores the potential for fandom in art, particularly from the perspective of transcultural, feminist, and artist-of-color fandoms.

As a result, we chose two fan concepts to bring together fanworks and artworks, curative and transformational fandom, which describe fans that primarily collect (“curative”) but also create fanwork informed by collecting that may challenge its source material (“transformative”). We examined the varied critical positionalities and emotional attachments of K-pop fandoms within these concepts.

Outreach and Art Historical Precedent

Rea McNamara’s table at a K-pop market organized by York’s K-pop club as part of our community-based research. We primarily engaged with local fandoms of third- and fourth-generation K-pop. These are idol groups that have been active since the 2010s, part of the Hallyu movement, to bands that debuted just before the pandemic, and are distinguished by their digital savvy and eclectic sounds. Outreach and engagement included an NCT-129 concert, as well as ENHYPEN and Aespa cup sleeve events. Photo: Rea McNamara.

During the winter of 2025, we circulated an open call for collections by actively participating in local K-pop communities, spanning student-led university K-pop clubs, K-pop online fan accounts, and K-pop shops.

K-pop fans come together in places like markets, where they trade and sell official and fan-made merchandise, attend pre-events for upcoming concerts, participate in K-pop dance choreography workshops and cup-sleeve events. (The latter are often organized at bubble tea cafes on an idol’s birthday or group anniversary, where fan-made cup sleeves are produced as commemorative print ephemera.) Toronto-area K-pop shops, like Koreatown’s Sarah & Tom, Dundas West’s District 9, and East York’s LightUpK, are brick-and-mortar storefronts that sell and distribute official K-pop merchandise and often host these events.

K-pop agencies sometimes forgo touring Canada to focus on the United States—and since Toronto is often the only Canadian tour stop for K-pop idols, concerts create a heightened sense of occasion, and attest to the importance of local organizing to sustain fandom communities. Granted, many fans are active online, maintaining Instagram “trading accounts” to buy and trade their merchandise, or chatting in Discords for university K-pop clubs. But they also earnestly participate in IRL social gatherings to meet other fans.

The K-pop concert remains the primary fandom experience: the chance to be close to its immersive, multi-sensory spectacle and be an active participant. Fans are even creative producers—adapting, remixing, and extending the meanings of a concert.

Long merchandise lines allow fans to cosplay their biases’ (K-pop fans’ term for their favorite group member) styles, or exchange self-produced and official photo cards, concert banners, and friendship bracelets as gifts with other fans. Concert-specific fan projects might include coordinating the venue-wide distribution of a concert banner or producing a venue- and group’s agency-approved fan-video screened during the concert. K-pop dancers might organize pop-up “random play dance” events outside the venue.

Through our interviews with the selected fan collectors—featured throughout this expanded text—we increasingly felt our own emotional attachments to presenting these objects and materials in their everyday context. Even as we were organizing this exhibition, we were still active fans in our own right, attending concerts (NCT 127) and documentary screenings (RM: Right People, Wrong Place). We sought support from our own K-pop fan group chat, affirming our desire and investment in having both fans and non-fans understand these fan objects through collectors’ own displays and handling of the materials, whether tabling at a fan market or home.

Yi Eungrok (Korean, 1808-after 1874), Books and scholars’ possessions (chaekgeori) detail, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Acquisition made possible by the Koret Foundation, the Connoisseurs' Council and Korean Art and Culture Committee. Re-mounting funded by the Society for Asian Art (Books and scholars’ possessions (chaekgeori)—Korean Folk Art).

It was crucial to situate these materials within an exhibition-making display strategy that resonated with their visual culture and aesthetics. The K-pop shelf and desk are common ways fans display their collectibles at home and in the office; online, Pinterest boards are also plentiful.

The shelf—often a white Ikea shelving unit—is a display with art historical precedent, reminiscent of bookshelves reverently captured in chaekgeori. The late 18th-century Korean still-life paintings featured “books and things”—the literal translation of chaekgeori—alongside other symbolic homewares and objects. These paintings showed a reverence for scholarly objects, a then-ascendant Korean cultural value, and became our own Kunsthalle for these fan objects.

K-pop Fan Objects and Gatherings as Exhibition Thematics

Installation view: Collection of Jo Saunders, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025. The display strategy mimicked the presentation of K-pop vendor tables at markets and cup-sleeve events.

Signed albums (StayC Sieun’s Teenfresh), lightsticks (2018 Red Velvet “Mandu Bong” with Wendy cap), fan project banner (Yves) and signed collectibles (Yeojin, Yves); various posters, photocards, and fan benefits from Gaeul (IVE) and Jo Yuri.

What prompted you to organize your own fan events?

“It started off with me just wanting to celebrate StayC’s fourth anniversary. So I did my own research and asked some other organizers how they put together their cup sleeves. From there, I could see what works for me and what doesn’t. So I put together the StayC cupsleeve and helped with some Red Velvet ones. And we also did the banner project for IVE.”

—excerpt from a 2025 Zoom interview with fan collector/event organizer Jo Saunders

Through our research, we connected with collectors who were active participants and organizers in local K-pop fan communities. While K-pop fans range in age, cultural background, and profession, we sought to identify commonalities that emerged within this particular group of fans.

The collectors in I came to ruin you were predominantly female, women of color, and first- or second-generation Canadians. Some were students into girl groups, dance covers, and fanart. Others were emerging arts workers and creative professionals who engage with K-pop to stay connected to their Asian diasporic experiences, or to make friends to attend K-pop concerts with.

The collections and artworks in I came to ruin you highlighted key fan objects and ways of gathering that define K-pop’s visual culture. They included:

“Bias” (Photo Cards)

Installation view (Detail): Photo Card Collection of Jo Saunders, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025.

Photo cards, also known as “PCs,” are collectible trading cards featuring K-pop artists, which were initially included in physical CD albums. These cards are often organized around a fan’s “bias”—their favorite member or group. The selection of a bias marks the beginning of a K-pop fan's journey, serving as a guiding light throughout their time in the fandom or a way of relating to other fans.

“Unboxing” (K-pop Album Packaging)

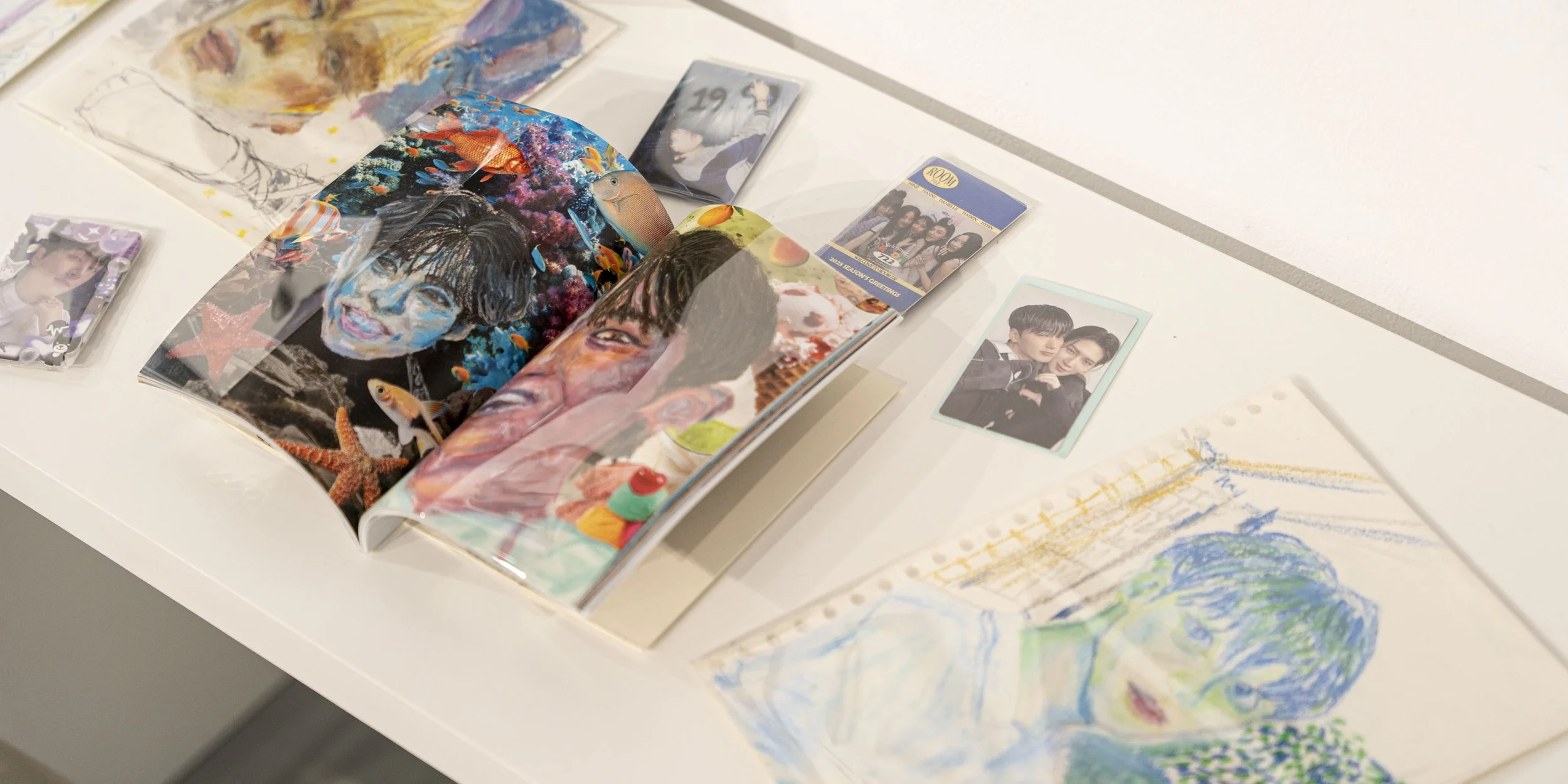

Installation view (Detail): Collection of Teodora Stojanovic, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025. Stojanovic, a collector and fanartist, inspired us to present her memorabilia and fanart in a desk installation.

Unsurprisingly, K-pop albums dominate physical album sales within the global music industry. These albums are renowned for their expansive print ephemera and innovative graphic design, becoming collectible artistic objects. (K-pop album packaging has garnered notice from the graphic design industry for setting music-design trends, particularly innovations in multilingual typography and cohesive design systems.)

The K-pop album can contain posters, postcards, photo books, and concept art, often packaged as a box set. Here, we “unboxed” a selection of K-pop albums to show how they become the centrepiece of a fan’s shrine, reinforcing their parasocial connection to the idol or idol group.

Performance (Dance Covers)

Installation view: Collection of Christine Kwong, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025.

Video documentation of the K-pop Club at York University’s dance covers of Jisoo’s “Flower Dance” and (G)I-DLE’s “퀸카 (Queencard).”

What motivates you to create a dance cover—is it the desire to faithfully recreate and master a challenging dance choreography, or is it a way for you to come together with other equally passionate K-pop fans to collaborate and create a dance performance?

“Personally, what motivates me is the thought that dance is a great form of physical exercise that helps maintain physical health, and relieves stress through music. I love expressing myself through dance—every time after dancing, I feel fulfilled and relaxed.

In the club setting, what motivates me to create dance covers is the thought of providing a welcoming space for students of all skill levels to dance, connect with others, improve their dance skills, and make friends. It feels like one big family when we can all laugh and have fun together at dance practice.”

— excerpt from a 2025 interview with Christine Kwong, fan collector and president of the K-pop Music Association at York University

K-pop fandoms also engage with performance documentation, including fan cams, fan-made videos, TikTok dance challenges, and official dance practice footage released by the groups. These videos go beyond merely following their idols—they offer fans a sense of control, transforming the fan from a passive consumer into an active participant.

Live Concert Experiences (Lightsticks and Concert Memorabilia)

Installation view (Detail): Collection of Sam Mohan’s TXT concert memorabilia, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025.

How do you participate in your local K-pop community?

“It’s primarily concerts and cup sleeve events. Many of my K-pop friends try to find more friends with whom to do things. ’Cause there are so many groups and sometimes you don't have a friend who stans the same group. So, through other friends, for sure. Work as well—surprisingly, I found a couple of other [co-workers] who are K-pop friends. That also makes work a lot more enjoyable.”

—excerpt from 2025 interview with fan collector/concert enthusiast Sam Mohan

K-pop concerts are powerful communal experiences for fans. Concert-related objects, including “lightsticks”—official portable devices that glow in sync with the music—alongside t-shirts and posters, create a strong visual connection among the audience. These ephemera serve as tangible markers of shared memories with the idol and the fan community, crystallizing specific stages of fandom activity. Some of these objects are even designed to symbolize an idol group’s connection with their fans, explicitly referring to the fandom.

Fan Productions (Fanart)

Installation view (Detail): Collection of Teodora Stojanovic, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025.

How did you prepare yourself for the concerts?

“I was ready for it […] I expected that kind of culture to be present there, like sharing things. I was hyped up for it, but when you hear the [fan] chants, it gives off … all those voices coming together. It gives off a sense of parasocial relations because it makes or breaks it. Because sometimes they’re right in front of me, and then it’s like ‘Oh, it’s not like some mythical being.’ You see them in real life, and it’s not bad; you just understand it. Or like [at a] P1Harmony [concert I attended, I saw member/vocalist Intak] somehow [get] close to where I was sitting. So I got to say hi to him and I was like, ‘Oh wow.’ So I feel those concerts can make or break parasocial relationships.”

— excerpt from a 2025 interview with collector/fanartist Teodora Stojanovic

Referring to fans’ amateur creative expressions, fan productions span a broad range of media types, including drawing, photography, video, craft, and fashion. In this art-production space, fans transition from mere consumers to creators, feeding into the K-pop ecosystem, where idols inspire fans, and fan-created content, in turn, influences the idols themselves.

Installation view: Collection of Teodora Stojanovic, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025.

Photocards (P1Harmony Theo tour, Jay [ENHYPEN], NewJeans, BOYNEXTDOOR, San & Yeosang), albums (ENHYPEN, ATEEZ, NCT, BTS), concert package (ATEEZ poster box set), and fan-created content (Our Season Zerobaseone zine, fanart of Hueningkai [TXT], Lee Seunghyub [N.Flying], and ENHYPEN members)

Artworks

Alongside the fan materials, we included art by artists who are themselves K-pop fans—perhaps even artist-fans—who have drawn inspiration from fannish methodology and brought that into their creative practice. In I came to ruin you, works by participating artists Jiwon Choi and Lux Pyre closely read, parsed, and critiqued aspects of fandom performativity and reenactment.

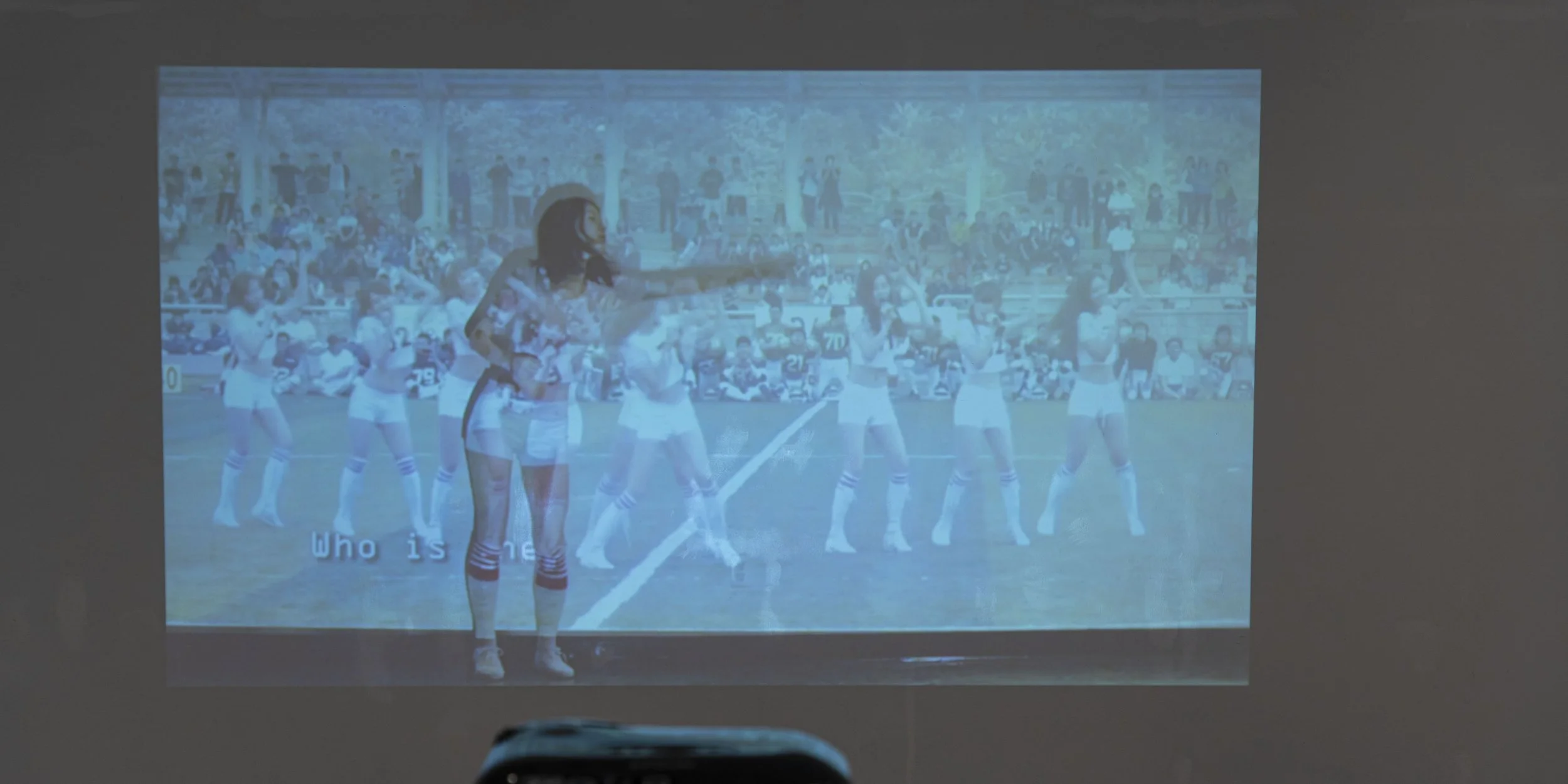

Installation view, Jiwon Choi, Generation’s Girl, 2014, I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

Through video and performance, Jiwon Choi offers a sharp and insightful critique of contemporary cultural dynamics, mainly through the lens of K-pop. Over the past decade, the Korean-born, New York City-based artist has blended traditional video-art techniques with popular media, creating a visual language that interrogates the intersection of K-pop culture and gender identity.

Excerpt from Jiwon Choi’s Generation’s Girl, 2014. Video performance, 3:20 minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

In her early video work Generation’s Girl (2014), Choi uses live projection to superimpose footage of the K-pop group Girls' Generation—captured during a South Korean football game—onto her body. The footage, featuring the group in cheerleader outfits, reflects the hyper-feminine roles imposed on women in the K-pop industry. By positioning herself within this spectacle, Choi critiques both the industry's objectification of women and the stereotypes imposed on her as an Asian woman, disrupting the male gaze within South Korea’s rampant sexism and gender-based violence.

Since Generation's Girl, Choi has gone on to create more work using K-pop as a lens to examine modern Korean history. In a series of TikTok-esque vertical videos, she performs as the members of her pseudo all-boy K-pop group, Boys on Top, who first appeared in her 2017 work Parallel.

This deepening engagement with K-pop's alternative, soft masculinities—seen in the “flowerboys” aesthetic—coincides with Choi's own queer identity. As a long-time K-pop fan, she marvels at how many current K-pop fans are openly queer. “These non-Korean fans are not afraid to speak up for who they are: ‘gays for ATEEZ,’ ‘lesbians for ATEEZ.’ I have seen a couple of fans come out to [the K-pop group ATEEZ] or telling them about their queer partners,” Choi said during a recent studio visit interview. “Isn’t that great how these bands know that queer people exist?”

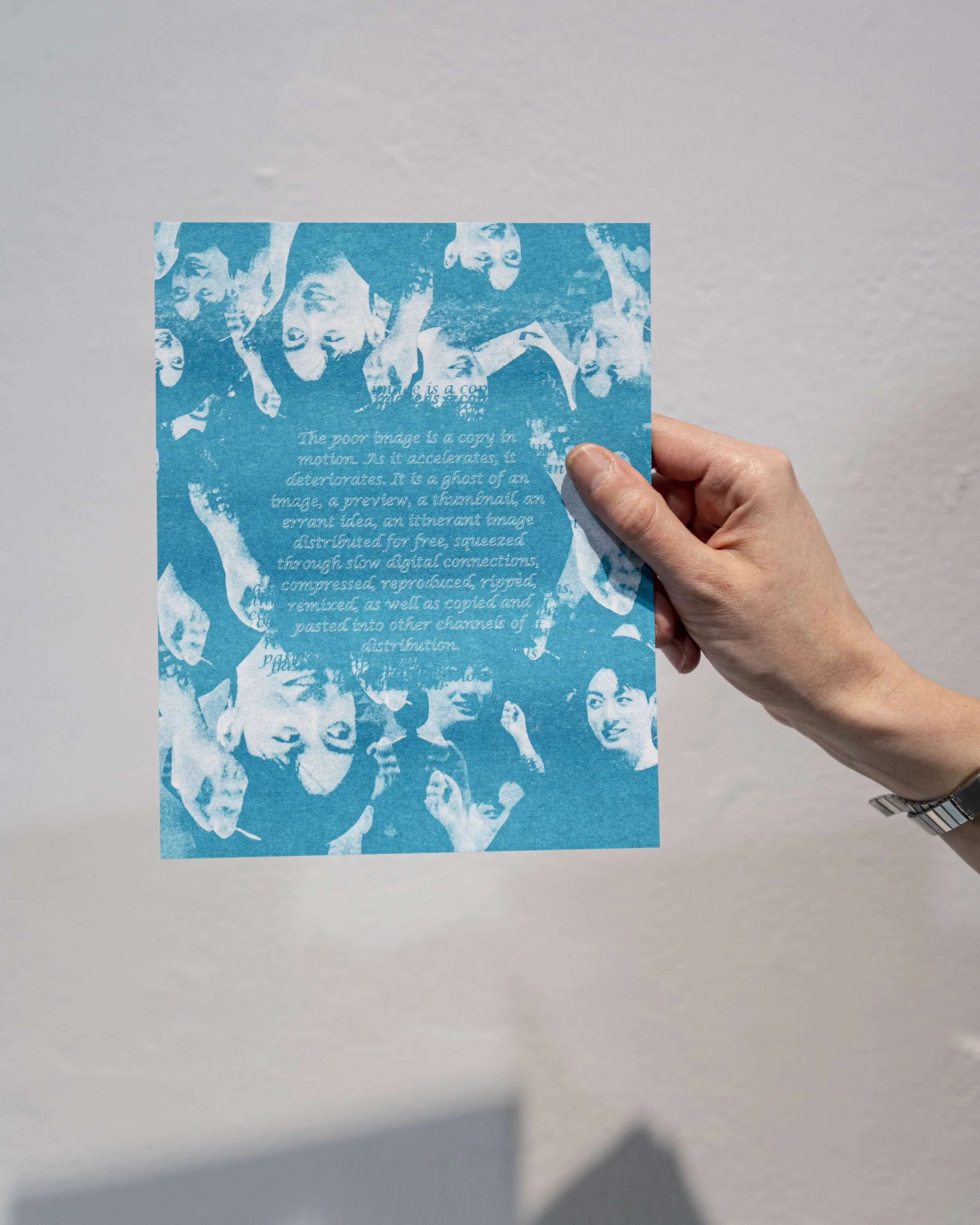

Installation view: Lux Pyre, the leaking, poor image (derogatory), I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

In online fandom, memes demonstrate a savvy form of circulated fan knowledge. Lux Pyre examines how ideologies and moralities are inscribed onto K-pop meme accounts' constructed narratives. His work explores intimacy, humor, and public spectacle in online and offline “communions,” predominantly through meme creation, as well as by organizing erotic live readings for queer performers in London, where he’s based.

Lux Pyre, the leaking, poor image (derogatory), I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

During the early COVID lockdown, Pyre became ARMY via real-person slash. His Instagram meme account, @outofcontextBTS, can be understood through the transformative fandom practice of shipping—which has been embraced by some performance artists as a relational approach to artistic practice. (See Fansplaining’s interview with Owen G. Parry, a visual and performance artist who discussed his work inspired by One Direction fandom.)

@outofcontextBTS is populated with headcanons about Pyre’s genderqueer interpretations of BTS members, including “milfseok,” a character based on BTS member J-Hope, imagined as a power lesbian femme. The portrayal originated from promotions for the “Butter” single, with J-Hope styled with a platinum blonde shorn cut and Balmain puff-shouldered blazer. For Pyre, “milfseok” is a headcanon with which he shares authorship with ARMY. “Him looking like a MILF—it’s a collectively-held archetype,” he says in a studio visit interview. “It’s co-created within the community.”

Pyre’s installation, the leaking, poor image (derogatory) (2025), includes his screen-recorded performance navigating the @outofcontextBTS meme account, which features multiple images of skinship, the Korean and Japanese term for non-sexual physical touch. In K-pop, skinship among members in an all-girl or all-boy group is often interpreted as evidence of shipping. While leaking, poor image surveys a range of imagined polyamorous pairings amongst BTS members, there is a fixation with “Jikook,” the ship name for Jimin and Jung Kook. At one point, the video lands on a July 3 2024 @outofcontextBTS posting featuring an obscured, somewhat blurry video of what appears to be the two members kissing, with the caption “a-are you sure?” alongside the hashtags #jikook and #jikookisreal. Like a headcanon, the hashtag #jikookisreal is a search term and portal into the alternate, relational reality that shipping affords.

Even within K-pop, fandoms can engage in toxic practices. The meme collage from Pyre’s leaking, poor image features a clandestine paparazzi shot of a smoking Jung Kook; the risograph multiple recalls the materiality of media fandom’s fanzine publishing history. Through this work, Pyre reflects on the gleeful, unruly irreverence of K-pop fans’ thirst and the fandom’s toxicity—an issue he has personally encountered as a fan who other ARMY doxxed, which has led to his increasing engagement with the “fervent, secret circulation within fandom of ‘bad images’ and ‘fake images,” he says, referencing the artist Hito Steyerl’s renowned text, “In Defense of the Poor Image.” Despite this experience, Pyre remains a fan of BTS and other K-pop idols, like the singer Taemin, a member of the second-generation group SHINee.

Photo Card (PC) creation workshop: opening event for the I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms, 2025. The well-attended workshop, facilitated by Ada So, invited participants to create and decorate their own PCs.

I came to ruin you: The Collecting Practices of K-pop Fandoms examined K-pop fan communities as spaces of cultural production and means of understanding contemporary identity, exchange, and artistic intervention. Through a curatorial approach that foregrounded fans’ methods of collecting and display, this project situated K-pop memorabilia within a broader history of material culture, from chaekgeori to digital archives.

By highlighting the creativity, passion, and collaborative spirit of K-pop fans, I came to ruin you recognized fans’ roles as cultural producers. Their collecting practices intersect with and challenge traditional art forms, transforming what might otherwise be considered ephemeral or niche into meaningful cultural expressions.

Acknowledgements

The co-curators wish to acknowledge the Crafting Community Project and Collective at Toronto Metropolitan University, the CIBC Fine Arts Graduate Student Award, York University’s School of the Arts, Media, Performance and Design, and the Faculty of Graduate Studies.

Thanks to Dan Adler, Marcus Boon, Anita Clarke, Colour Code Printing, Jennifer Fisher, Tony Halmos, YongTaek Kim, Zoë Martin, Rian McNamara, Quincy McNamara-Halmos, Ken Moffatt, Chloe Panaligan, Jennifer Park, Ada So, Sydonnae Symone and Christine Thomson for their support.

Further Reading

Ahn, Patty, Michelle Cho, Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, Rani Neutill, Mimi Thi Nguyen, and Yutian Wong, eds. 2024. Bangtan Remixed: A Critical BTS Reader. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478059615.

Grant, Catherine, and Kate Random Love, eds. 2019. Fandom as Methodology: A Sourcebook for Artists and Writers. Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar: Goldsmiths Press.

Kim, Suk-Young. K-Pop Live : Fans, Idols, and Multimedia Performance. Stanford University Press, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503606005.

McNamara, Rea. 2021. “How BTS’s Internet Presence Feeds ‘ARMY’ Meme Production.” Hyperallergic, January 22, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/615256/how-btss-internet-presence-feeds-army-meme-production/.

Voon, Claire. 2017. “The ‘Shelfies’ of Korea’s Joseon Dynasty.” Hyperallergic. October 31, 2017. http://hyperallergic.com/400785/the-shelfies-of-koreas-joseon-dynasty/.

If you liked this piece, please help us publish more things like it! Become a patron for as little as $1 a month, or make a one-off donation of any amount.

Rea McNamara is a writer and curator based in Tkaronto/Toronto. She has curated and programmed for The MacKenzie Art Gallery, The Gardiner Museum, and Vector Festival, and has written for Border Crossings, Hyperallergic, Frieze, and more. Currently, she is an SSHRC-funded MA candidate in York University's Art History and Visual Culture program. You can find her on Instagram, Bluesky, and Linktree.

Bo Shin is a conservator based in Tkaronto/Toronto. She currently works for the City of Toronto and has held roles at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Science Museum of South Korea, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. She trained at Fleming College and Queen’s University, with a focus on preventive conservation, collections care, and exhibition support.