Episode 139: The “Q” is for “Queerbaiting”

In Episode 139, “The ‘Q’ is for ‘Queerbaiting,’” Elizabeth and Flourish dig into the thorny concept of “queerbaiting”—when creators tease at queer relationships in their shows and films but fail to follow through. Topics covered include disconnects between creator and audience expectations, fans’ conflation of shipping and representation, and shifting attitudes and norms in television writing and marketing. Plus: they read several listener responses to the previous episode, giving context to Destination Toast’s stats on AO3 fanfic production in 2020.

Show Notes

[00:00:00] As always, our intro music is “Awel” by stefsax, used under a CC BY 3.0 license. Our cover is from the immortal Vine:

[00:02:00] We spoke with Destination Toast in Episode 138.

[00:02:53]

[00:09:00] Our interstitial music is “A History of Bad Behaviour” from Music for Podcasts—True Crime Edition by Lee Rosevere, used under a CC BY 3.0 license.

[00:15:14] The first half of this video is Castiel’s death scene (spoilers, obviously):

And you can watch the same scene in the Spanish dub here.

[00:33:24] Episode 17, “The Powers That Be.”

[00:37:08]

[00:40:14] Aja Romano’s recap of the Supernatural series finale.

[00:42:15] One of the many places you can read about Supernatural’s popularity through the U.S.: “‘Duck Dynasty’ vs. ‘Modern Family’: 50 Maps of the U.S. Cultural Divide” from the New York Times.

[00:43:44] The Hollywood Reporter did a great retrospective on Supernatural’s ratings.

[00:44:45] OK, a little more context:

Twin Peaks had 36 million viewers for its pilot episode in 1990. Its least-viewed episode had 7.4 million viewers.

Compared to Twin Peaks—in 1990 Cheers was regularly receiving 36 million viewers.

In 2019 the Super Bowl pulled in approximately 98.9 million viewers, the Oscars got 30.5 million, and The Big Bang Theory’s finale got 25 million viewers. (Numbers from Variety’s 2019 year-end review.)

[01:05:16] We cover our Shipping Survey in Episode 97 and Episode 99, and there’s more on our Projects page as well!

[01:08:35] We featured Javier Grillo-Marxuach in Episode 82.

Transcript

Flourish Klink: Hi, Elizabeth.

Elizabeth Minkel: Hi, Flourish!

FK: And welcome to Fansplaining, the podcast by, for, and about fandom!

ELM: This is Episode #139, “The ‘Q’ is for ‘Queerbaiting.’”

FK: [laughs] This is a topic that’s always on our minds. It’s particularly on our minds right now, I will admit.

ELM: I’m sorry, it’s not always on my mind. That is overstating it.

FK: Often.

ELM: This is, I think, like our slash episode, this is like a perennial topic that lurks in the background of discourse, and this is apparently the—not even year, like, the season of pulling off the Band-Aids of the topics that we kind of dance around and didn’t actually want to devote episodes to. But some recent events have led us to feel we needed to pull off that Band-Aid.

FK: Yeah. All right. Before we get to that though, we should deal with some business from our last episode, in which we had Destination Toast on to talk about 2020 fandom stats. Because in that episode, we and Toast had many unanswered questions about what was going on in 2020, and some of you—dear listeners—had answers.

ELM: You’re so cheesy.

FK: I know. I love it! You love it too.

ELM: Nope! Only one of us loves it.

FK: [laughing] You…put up with it.

ELM: Yep! Tolerating it right now. OK. So, yeah. The numbers were very interesting and there were a few different things that we just had no idea about, and we hoped that people would fill in these blanks for us. So which one should we do first, the games or language stats?

FK: Let’s do games. So one of the questions we had was, why is it that Minecraft is suddenly this fandom that’s like, popping? There were a couple of other game fandoms that we had this question about too. But I believe that you reminisced about the time that you played Minecraft, and a very small child made you chop wood for hours?

ELM: OK, I don’t know what Minecraft is like generally for a normal person.

FK: [laughing] How do you write fanfic…? You had questions.

ELM: In my experience, it was me and a seven-year-old, and he pitied me so much, and everything was—it was like The Sims with less plot, we were just in a kind of a brick-based, like a cube-based landscape where you kinda had to build a little house and collect little things, you know what I mean? There’s no narrative. So that’s why I was really curious, what is the fanfiction in this place? But I also, obviously my experience was so limited, being shamed by a seven-year-old. I mean, it’s probably also a very common experience amongst some older people.

FK: Right, right. But there were actually, so there were two answers that people brought to us, and one of them was one that we had already come up with. I think it was even you who came up with it.

ELM: No, that wasn’t me, that was you. Take it!

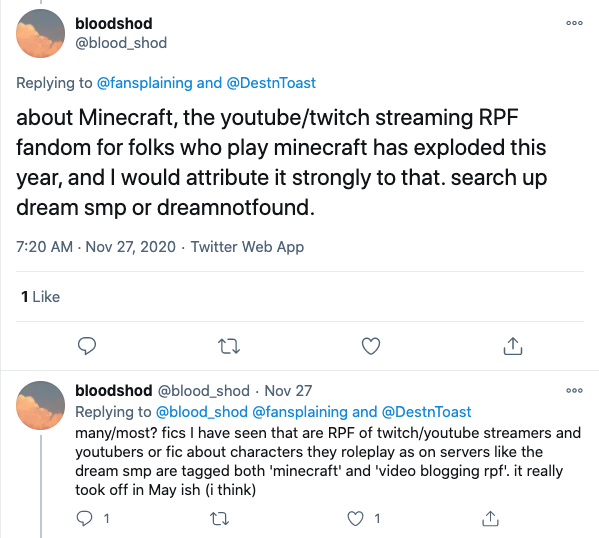

FK: It was me? Oh wow, that’s great, I was so smart! @blood_shod on Twitter says, “About Minecraft, the YouTube/Twitch streaming RPF fandom for folks who play Minecraft has exploded this year. Many or most fics that I’ve seen that are RPF of Twitch/YouTube streamers and YouTubers or fic about characters they roleplay are tagged both ‘Minecraft’ and ‘video blogging RPF.’ It really took off in May I think.”

So that was one explanation, but then @nyxmidnight on Twitter gave us another one too, which is: “Minecraft’s main character is now a playable character in the huge Nintendo fighting game Super Smash Brothers Ultimate, so the character’s reaching a whole new and broader audience it never would have otherwise.” And I’ve seen plenty of Super Smash Brothers fanfic, I know how that stuff gets written, so that makes sense too.

ELM: It’s probably both!

FK: Why not both!

ELM: No, seriously! I mean it’s actually interesting too, you could probably—if you were very enterprising and this was your fandom, you could break those numbers down if you truly wanted to, you know?

FK: Maybe someone will truly want to.

ELM: Yeah, anyone in the Minecraft fandom, tag us. Let us know if this is a fun analysis question for you.

FK: OK, but what about the other one? There was—we had some questions about language stats, also.

ELM: So one of the most interesting things Toast saw in the stats overall was that fanwork production was way, way up, but also there were some like, kind of huge spikes in the month-to-month, and it was kind of a weird graph, and it was also something that we couldn’t really wrap our heads around, because Toast had broken things down by language, and there were big spikes in July, I believe.

FK: Yeah, it was July.

ELM: On the whole archive. And the spikes were not happening when you just narrowed it down to English language, which is by far the most popular language on the Archive, nor in Mandarin, which is the second-most popular. But they were happening in I believe the next two most popular languages, or up there: Russian and Brazilian Portuguese. So we were like, “Uh? Something happened? Brazil and Russia in July?”

FK: [laughs] Yeah. “Were there lockdowns then? We don’t know!”

ELM: That was us, a few weeks ago. Turns out things were happening but they weren’t about the coronavirus, they were about fandom. This letter was extremely fascinating, and I’m so glad we got it. So, do you want me to read it?

FK: Go for it, yeah, I’d love to hear it.

ELM: OK. So the letter is from Nary Rising.

“Hi Elizabeth and Flourish, thank you for making such a consistently interesting and thoughtful podcast! I think I can shed some light on a few of the stats questions from your most recent episode. (Disclaimer: I’m one of the chairs of AO3’s Support committee, but I’m just speaking for myself based on things I’ve observed from that vantage point, so please don’t take this as an official statement! Nor am I a Brazilian or Russian speaker so I might have certain details wrong!)

“The language bumps of Russian and Brazilian Portuguese are, I think, somewhat explainable based on migration of certain groups of fans. In Russian-speaking fandom, there is a huge twice-yearly challenge called Fandom Kombat.” That’s “Kombat” with a “K.” “Previously they were hosted on a different site, but this year they have moved to AO3. Its Summer 2020 round got 7500+ works, so that on its own is a big spike of Russian-language works around July (the collection opened July 1 but works could be posted over a longer span of time). The mods of the challenge have also been bringing over all of their previous years’ works, which would contribute to an overall growth in Russian fanworks this year.

“Meanwhile in Brazil, a major Portuguese-language fanfic site, Spirit, introduced a new paid tier in June, and also experienced a crackdown on non-allowed works. For instance, pornographic works are not allowed there, but their policies are inconsistently and sporadically enforced according to users. Here's their guidelines in English if you’re curious!” We’ll link that in the show notes. “They also remove stories for bad grammar, for instance.” Which is wild to me. I don’t know how you do that. I mean, I could do that. But.

“As a result, some Brazilian BNFs moved their works to AO3, and presumably their readers followed. I gather there were also some efforts to make the Archive more accessible to Brazilian users, such as fan-made guides in Portuguese on how to use it, which might have contributed to an increase in use. (Incidentally I believe Spirit is very big in K-Pop and Anime fandoms, so if some portion of their users are migrating that might also boost numbers in those types of fandoms!)

“On the tag wrangling questions (like “why isn't K-Pop RPF?”) the simplest answer is that at a certain point, tags get too big to move. So even if tag wranglers (and users!) might love to see greater consistency in what is or isn’t subtagged to RPF, when a tag has hundreds of thousands of works, it is really, really difficult to move, both because of technical limitations and just the sheer inconvenience it would cause to users. Thus do our past choices haunt us.

“Open Doors has not imported any Naruto or other big anime fandom archives in the past year, so I think any increase in those fandoms is purely user-driven. Anecdotally I would say there have been more complaints this year about technical issues at ff.net driving people to move their works, but I don't know if that’s enough of a factor on its own to explain the increase in older anime fandoms. I do think the Netflix factor probably contributes—personally I watched Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood this year purely because it was now on Netflix, so I’m sure other people are in the same boat—either discovering classic anime that they hadn’t watched before, or going back to old favourites that are now conveniently available.

“All the best, Nary.”

FK: Wow. That is a letter that is chock full of news we can use.

ELM: I’m usin’ that news right now. This is really…

FK: I am using it.

ELM: Yes.

FK: Thank you so much, Nary. That was amazing and explained many things.

ELM: Extremely illuminating. If any of that didn’t make sense, I would say, cause we just talked about the spikes, but there were some other questions we had too that Nary illuminated there, so I would say go back and listen to the Toast episode if you haven’t heard it yet, because this is like—some of that context!

FK: Excellent.

ELM: We coulda used. Before we had that conversation. We didn’t know. This is the point!

FK: Yeah!

ELM: We put the questions out, we get the answers!

FK: Yeah, it’s great! It’s wonderful! Fandom is wonderful in that way: you put the questions out, most of the time you get the answers! Sometimes you don’t get the answers.

ELM: No, a lot of times you don’t get any answers. But yeah, this is really helpful. We had other questions too, we’ll take any answers, we’d love to share them with people. So thank you to Nary and to our Minecraft fans who Tweeted at us. Really appreciate that.

FK: All right. That business having been taken care of, shall we take a quick break and then wander over to the land of queerbaiting?

ELM: Just thinkin’ about that Band-Aid. Rippin’ it off.

FK: All right. See ya in a sec.

[Interstitial music]

FK: All right, we’re back. Before we talk about queerbaiting, let’s quickly talk about Patreon. So, as you probably know, this podcast is supported by listeners and readers like you via Patreon. You can support us by pledging at patreon.com/fansplaining. There are a bunch of different levels you can pledge at, from like, $2 a month or even less, all the way up to $10 a month. We will also accept more than that but, you know.

ELM: Less than $2. That’s $1.

FK: Yeah, you know. OK. Anyway, there’s levels! There’s levels, there’s levels. You can get all sorts of stuff from that. We’ve got like over 20 Special Episodes for patrons only, for example, including we had a series of Tropefest episodes where we talked about fanfic tropes. We did a series about the Emmy-nominated shows this year, three of the Emmy-nominated shows that we talked about at length. We’ve also got cute enamel pins, you can get your name in the credits…we mail out a Tiny Zine for $10-a-month patrons. We actually have some from this most recent round, so if you pledge $10 a month, you will receive one of those, and it will be exciting, and it’s all about how much Elizabeth loves Rupert Giles.

ELM: Yes. 14-year-old me, 35-year-old me.

FK: Indeed. OK. But that’s not the only way that you can support us. If you don’t have any money, we totally understand.

ELM: No! It’s my turn to take over now. You can’t just say it all.

FK: I was trying to give it to you! I was trying to hand it to you, but you weren’t saying anything, so I was like “OK, I’ll try and give you a little lead-in.”

ELM: Jesus Christ. Did you ever play basketball? I’m not sure that you did.

FK: I’m bad at team sports. [both laugh]

ELM: That explains it. All right. So, yes. You do not have to give us money. We know it’s a really, it’s a very difficult year economically for so many people, and so it’s something we’ve been stressing throughout this year: absolutely no worries. Even if you have pledged to us and you have to knock down the level of your pledge or cancel your pledge or put it on pause, we absolutely understand.

So if you don’t have any cash right now, no worries at all. The most important thing you can do is get the word out about the podcast. That means subscribing, so we get boosted kind of in the way we show up in various podcatchers, podcast platforms. Sharing our transcripts or the audio—but especially transcripts. There are so many people in fandom who we see, you know, in our tags and notes. Now Tumblr tells you what people are tagging in the reblogs of your post, which I don’t like this change, but we do see plenty of people saying things like “Oh, I never listen to podcasts, but I’m curious about this,” and we have these full transcripts! So you know, it’s not just a podcast. We are a media outlet of sorts.

FK: [laughs] Wow.

ELM: We are! We have articles too. You know? Like, we had a media, you know, empire actually! Empire.

FK: Empire.

ELM: Also, you could get in touch with us! You could be like our Minecraft and AO3 writers-inners. [laughs] You can write us at fansplaining at gmail dot com, you can leave us questions or comments, fansplaining at Tumblr, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook. You can leave us a question at fansplaining.com. That one, as a friendly reminder, we like to say occasionally: if you would like a response to that, you need to leave your contact information. Most people do not, and sometimes we have questions about their questions, and have no way to follow up. And finally, most excitingly I think, you can leave a voicemail. That’s 1-401-526-FANS. You don’t have to say your name, just say you wanna remain anonymous or just don’t say anything at all, and use your voice, and we’ll put it on the podcast!

FK: All right! You’ve come to the point where the Band-Aid has to come off, Elizabeth, we’ve gotta talk about queerbaiting now.

ELM: You’re right. I suggested this episode topic, so in fact I am being petulant about something that was my idea. That’s fine. So, it’s Saturday after Thanksgiving. It’s like Day 20 of the Supernatural finale.

FK: [laughs] Yeah, we rolled out of the election right into the never-ending Supernatural finale.

ELM: It’s just constant. I imagine most of our listeners will either know what’s been going on or have actively chosen not to know. But my very brief summary is this: the CW’s Supernatural, a show about two brothers who drive a car.

FK: And their angel friend.

ELM: Yes. Who arrived somewhat later, but is extremely important. Been on the air for 15 years. Extremely long-running show, you say, on the CW, a network that brings you a particular kind of show. [FK laughs] For a very long time, one of if not at certain times the largest fandom in the sort of transformative, Tumblr, like, that kind of space.

FK: It was the largest for a long time.

ELM: Right. I think it has been overtaken now by, definitely by Marvel.

FK: Yes, yeah yeah yeah.

ELM: If not a couple other things too, of that nature. But still, for a TV show also too, I think, probably the largest TV fandom.

FK: It’s punchin’ above its weight class, let’s just say.

ELM: Absolutely. So after 15 long years, they announced last year that they would be doing the final season, and it started to air, and then I know they had some trouble filming the final few episodes because of coronavirus limitations, and the third-to-last episode aired two nights after the U.S. presidential election, while we were all desperately waiting for a certain few states to announce their results. And one of the members of the most popular ship said “I love you” to the other one.

FK: Yes.

ELM: And then was sucked into super Hell.

FK: Yes. He was specifically sucked into super Hell because it gave him ultimate happiness to save the other one’s life.

ELM: Right, and it was a big world-ending moment, like, it was the ultimate sacrifice, right?

FK: Yes. Ultimate sacrifice. Also an insta-Bury Your Gays. A little bit.

ELM: Yes. OK. So then there’s that and, you know, this is relevant to this conversation, but the other one who was, who received the “I love you,” said “Don’t do this.”

FK: Yes.

ELM: And then whoosh, into super Hell.

FK: Yeah. And the “don’t do this,” specifically, was in context not about “I love you,” it was about “don’t send yourself to super Hell.”

ELM: [laughing] Sorry!

FK: Let’s be really clear!

ELM: I understood out of context how that could sound. It was, “No! Don’t say those words, stop.”

FK: That’s not what it was! It was “Don’t send yourself to super Hell.”

ELM: OK. And then there was another episode, I don’t really know what happened in that one, and then there was a final episode and it was in that final episode which aired two weeks later—Joe Biden was winning the election for the 15th time by that point, every time a new state got called or certified or something we had to celebrate all over again—and people were really expecting some sort of re-emergence of the character that got sucked into super Hell and some sort of explicit romantic confirmation of this relationship.

FK: Right, because the previous episode sort of wrapped up all these loose ends from the series, and so then you were like “OK, great, so there’s like a final episode, so…what’s gonna happen in this final episode? Something happy that checks in with all these characters, right?” You know.

ELM: And then…I like how I’m telling what happened and I haven’t seen this.

FK: Yeah, but I’ve told you about it so many times that you can do it by heart. You’re doin’ great so far.

ELM: This is the faster way to do it. So there were some vampire clowns and then Dean gets nailed by a nail.

FK: He gets killed by a piece of rebar and he dies, in the way that he always said that he wanted to do, which is going out fighting.

ELM: But not dramatic fighting. I’ve seen a lot of longtime fans being very disappointed that it wasn’t a sort of like saving-the-world kind of death, just…

FK: Just some vampires, and there was an error, and he died.

ELM: Vampires in a barn. And that’s somewhat early in the episode and then you see his brother Sam’s life journey, his blurry wife, his child, his old age deathbed, and then he dies and goes to Heaven and is reunited with his brother Dean and you find out that Castiel, the angel who went to super Hell, is in Heaven also, but you don’t see him. The end.

FK: Correct. That’s happened.

ELM: [singing] Carry on my wayward son…

FK: Yes, then “Carry On My Wayward Son” plays, because that is how it had to end.

ELM: So that’s where we were as of 10 days ago. No. Was it that, was it only 10 days ago? Was it actually two-and-a-half weeks ago? No. It was only 10 days ago.

FK: [laughs] It seems like forever. But then! Then, a bunch of other stuff has happened since then.

ELM: Ok.

FK: The biggest thing that’s happened since then is that the Spanish dubbed version of Supernatural aired and in the dub Dean says “I love you” back. Which obviously made everyone lose their ever-loving minds.

ELM: Well, OK. Step back a little. So in the intervening week, between the American homophobia and the Spanish gay love… [FK laughs] There were a huge range of reactions, and I should say that like, while Destiel is by far the biggest ship here, there are a lot of people who don’t ship that, right? And also there are a lot of people who are extremely invested in Castiel as a potentially queer character, or Dean as a potentially queer character, and not necessarily in the canonization or consummation of a ship, but rather in their individual fates. And obviously, you know, their romantic fates as well, but I—I don’t mean to say that to diminish the ship, but like, I think that there were a lot of people who were truly upset about the individual fates of these characters.

FK: Right, which is reasonable, because I think that there’s—there’s lots that you can—like, I got notes, you know what I mean? There’s lots you can say about this.

ELM: Right. That being said, there were a lot of people who I saw who really enjoyed it, you know? Feeling like it had come full circle. I saw people say…

FK: Yeah.

ELM: Responding to the same full-circle-ness, “There’s absolutely no growth if you wind up in the same exact place where you started,” et cetera, and other people read it as a tribute to the beginning…you know, obviously you could say, you could read into that what the writers were intending, and that might make you unhappy, but that was an intentional choice on their part.

FK: Yeah, exactly. I mean, I can say that like, as a person who—I literally watched the first season of Supernatural as it aired on the CW when it was on the air, and have watched ever since, and like, it seemed clear to me that they were making a choice to go back to the beginning, and I enjoyed certain aspects of that. But it also totally makes sense that it would be frustrating.

ELM: Right, right.

FK: It’s one of these things where I think that there are a lot of different perspectives on Supernatural, and as many perspectives as there are on Supernatural, there actually are that many perspectives on the finale. [laughs]

ELM: Right, right. So you know, it was a tricky one to analyze after the fact, and the additional group of people weighing in on this was probably potentially a larger group than even current fans of Supernatural, which is either people who had passed through the fandom at some point and like, kind of left in frustration, or huge numbers of people who have never been in the fandom, have never seen the show—I mean, I say this as someone who hasn’t watched this show. You have watched all 15 seasons, I have watched zero, though I have read multiple books about this fandom.

But tons and tons of people either earnestly weighing in on what they believed happened in these final episodes, or a huge number of people dunking and shitposting and saying like, “This fandom is funny, this show’s funny, how goofy, I’m gonna make these jokes,” some of which I know were embraced by some Supernatural fans, some of which I think people were bristling at because they were upset about what had happened or they were happy and didn’t want to see it made light of. So like, that was—it’s been, you know, a huge, huge amount of volume of social media posts on this stuff.

FK: Right, absolutely. So this, this feels like a huge conversation, and it feels also like it’s been really dominated by this question of like: what is going on? Have we just all been queerbaited for like 15 seasons on this show? That’s a huge, you know, tons of people being like “This is queerbaiting, we were queerbaited, this sucks.”

ELM: Hang on. So we should define what “queerbaiting” is, but I wanna say, as we define it, that for the last 10 years or so, right? Maybe 9 years? Since Castiel showed up, if you were to ask broadly people in fandom—this kind of fandom—like, “what does queerbaiting mean?” and had to give an example, there are maybe three examples that they would bring up, and this is one of them. Right?

FK: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

ELM: Like, for context, if I had to name a second one, it would be BBC Sherlock, right? You know? And there are others that are very famous. But if you had to ask some random person who had never seen this show before, but was in fandom, like, “What’s queerbaiting,” they’d be like “Oh, you know, like, what Supernatural and Sherlock do,” right? You know? So like…

FK: Right, right.

ELM: This has become kind of a shorthand. But all the while, I knew plenty of Destiel shippers that would say things like “Well, this isn’t queerbaiting because it’s gonna happen. It’s not baiting if eventually you deliver on the queerness.”

FK: So what is baiting then? So I think that if I were gonna try and define “queerbaiting” without reference to any fandom, I would say: queerbaiting is what happens when you have a show with two male characters that people start to ship them, and the writers notice, and they start writing in wink-wink, nudge-nudge, arguably kinda gay scenes without any intention of having those characters actually be gay or in love with each other or anything like that.

Just from the writers’ perspective I think, usually, the idea is like, “Oh, we’re giving a treat to the fans. We’re never really gonna do this, but they like seeing it, so let’s give it to them.” And from the fans’ perspective, obviously, it’s like, “Wow. They’re signalling that they’re going to get these people together and then they never do, and that really sucks.” You know? “They conned us into watching this whole time, and it was never actually a pairing.”

ELM: Beyond, yeah, and I would say beyond the actual text of the show there’s a few other things that get classed as queerbaiting—one within the shows themselves, sometimes I think the actors can play this up, right? Because they have a little bit of leeway, right?

FK: Like, I mean, you could argue that Poe Dameron is a great example of like, “Hey, he loves Finn!” Right?

ELM: Yes. Right, exactly. And then beyond the actual content of the show or film or whatever, you have two different extratextual things going on. One is commentary from the writers and actors, you know, whether it is something like—not to pin it all on Oscar Isaac, because lots of actors do this—whether it’s like “Yeah,” whether it’s teasing or sincere, “I think they really love each other!” You know. And it’s like, “OK. Are you telling us what’s going to happen, or this is your opinion, right?” Or, the very famous kind of showrunner response of like, “Well, you’ll just have to tune in next week and see,” you know.

FK: Right.

ELM: It’s like, no! Don’t! That’s truly baiting, because it feels like you’re deliberately being strung along. There’s that, and then there’s often completely disconnected in terms of strategy, but there’s the people who run the marketing accounts who may see fan response to this stuff and then play it up in social media—having almost little-to-no connection to the actual people making the show.

FK: And sometimes that can be intentional and sometimes it’s not. Sometimes they actually have an idea what they’re doing. I worked on a project where the previous social media people had stumbled across a smush ship name but didn’t know what it meant.

ELM: Flourish.

FK: And had used it, because it sounded like a joke about a holiday.

ELM: No!

FK: And they had used it because they thought that it just referred to this one character and the holiday, and then they were like, “Wow, it got such great—it got such great numbers!” It was like, “Oh. Oh boy, you are incompetent.” [ELM moans] But then there’s also times when people have like, purposely done it. I mean obviously BBC Sherlock is an example, but Teen Wolf is another example, another really early example of like, social media person is like, “When I play with the shippers, my numbers go up, and that’s good for my job.” You know? And then, you know, that’s a long-term bad strategy, because they don’t necessarily know what the writers have planned or have anything connected.

ELM: Right, and I also, I mean, we’ve seen this too in like—obviously I think that Twilight really set the kind of, this sort of template of “Well, we can—if there’s a potential triangle,” right. Like, treating it like some kind of game, “Which ship is gonna win.” We’ve seen, I remember The 100 before they killed Lexa was engaging in this, but it was pitting a queer ship against a male/female ship, and it was just like…OK, it’s a little different [laughs] when you do it this way, when it’s not just which dude will this lady choose, but you’re actually pitting…

FK: Right.

ELM: You know, et cetera. That kind of thing. So I think that…

FK: Yeah, in my dream non-homophobic world where everything is candy and flowers, it’s not different. But it is different, because we don’t live in that world.

ELM: It’s different in 2015 or whatever year that was, you know? Like, sorry. We are not there yet. So it’s that kind of thing, but I think that people can say, like, they can look at this stuff and say “look at the engagement, I’ll keep doing this,” without realizing that you know, with very limited—you know, still an extremely small proportion of characters on TV are queer. So it’s not fun and games at that point, you know.

FK: Yeah.

ELM: Like it might be for a Ross and Rachel kind of will-they, won’t-they sort of thing, where you assume they will because that’s the way that most media turns out.

FK: Right, right. And frankly I mean, I think that’s gonna continue for a while, right. People who are starved for queer media when they’re young—even if we suddenly have 50 versions of The Happiest Season—all of which have different takes, so if you didn’t like it or if you loved it, either way, you can…even if we had a glut of this stuff, I think there would still be people who felt like, who felt very defensive of it. Because when you’ve been operating from that point of starvation for so long, it’s really hard to check yourself and be like “Oh, wow, actually there’s these other options out there.”

ELM: Yeah, yeah.

FK: So I don’t, I think that it’s both things. I think it’s both there’s not that much right now, but also even when there is I think that people should not expect folks to react the same way.

ELM: Yeah. OK. So that’s what queerbaiting is. The reason we’re framing this around Supernatural is that’s what’s been happening for the last few weeks. So to put that definition back into this context, what it’s really become to me—observing the way a lot of people are talking about this is, initially… I think that it’s evolved a little bit beyond that now. But it’s the idea of whether it was baiting or not hinging up on whether the, like, love confession meant that the ship was canon or not, right? And if it wasn’t, whatever that means, because I think that’s in the eye of the beholder somewhat, then that’s either baiting or it’s confirmation of the thing that’s been going on the whole time, right?

FK: Yeah. I think that then, like, the conversation has almost shifted, though. Which is weirdly, lately, I don’t know what you’ve been seeing, but I’ve been seeing much less annoyance at queerbaiting and much more, like, “Ah! We found the proof,” right? “Oh, we won, we found the proof, this is real.” Particularly since the dub came out, but even before that, I felt like it was shifting into this idea of…almost like an antagonistic relationship between the fandom and…I’m not sure who the antagonist is, frankly.

ELM: The network!

FK: Yeah, I guess the network. And I guess that then in between those two things, the writers or the canon? Maybe not even the writers, but whatever the truth of the canon is, right. This fanciful truth which I don’t—for context, I don’t think that there is a truth. The only way that Dean, Sam and Castiel exist is in our minds and in the things that writers have written, so it’s not like there is a Dean or a Sam or a Castiel out there in a sort of, you know, parable of the cave kind of way. You know? [laughs] Like, there is no form of the Castiel who actually is gay or form of the Dean who actually is bi! That’s not how this works, right? But people have this idea that there’s some true Dean and if we could understand true Dean, then Dean would be bi, and there’s proof that he is.

ELM: Right, right. So I don’t wanna go too deep into fandom conspiracy theories. I actually would like to do an entire episode on this, I feel like that is also a massive Band-Aid that we’ve hesitated to pull off. I feel like I personally have had some hesitance to talk about fandom conspiracy theories publicly because I witnessed so much abhorrent behavior in the Sherlock fandom, and a lot of that was around a conspiracy theory—though it’s been, you know, five years now, and I guess with a little bit of distance it actually makes me somewhat of an authority on how conspiracy theories can play out in some fandom contexts, so that’s great. It was great to have that first-row seat.

But I don’t wanna talk too much about it because I don’t think that all fandom conspiracy theories, despite giving those two examples which connect to queerbaiting, I don’t think a lot of them actually have to do with queerbaiting, right? But there is always an element of finding out the truth.

FK: Right.

ELM: I think that’s where they connect, curiously, this idea of “there is some truth.” And you get this kind of circular thinking where you say, “Well, it can’t be baiting, because it’s true.” Right? It’s a kind of defensive way of protecting yourself to say like, “I don’t want this show that I love to have been fucking with me for so long—”

FK: Right.

ELM: “—to have been teasing me. I refuse to believe that that actually,” and you know, I can’t speak to Supernatural and I’m not in this fandom. I obviously have had a ton of it on my feed in the last few weeks. But in Sherlock I remember people saying things like, you know, in Season Four as it was coming out, saying things on my dash like “If it doesn’t happen, if John Watson and Sherlock Holmes don’t kiss in an extremely obviously romantic,” I don’t know what kind of non-romantic kiss they would have, but you know. “If it’s not clear that they are romantically involved in that way, sexually involved, then maybe this show is kinda homophobic.” [FK laughs]

And it’s like, “Ding ding ding!” I don’t know what to tell you! That’s, or even some people saying like, you know, “If this isn’t true, then actually some of this writing was pretty bad.” And it’s like, yeah! Sorry, no shit, Sherlock, this writing, in the fourth season, was bad! I’m gonna say it. I know some people liked it, sorry, I have friends in this fandom who thought it was good. But like…it is very weird to me because it’s like, the canonicity of your ship doesn’t make the writing of the show better or worse, in most cases. And I say this having had two canon queer ships: it didn’t dramatically make the writing suddenly better or worse, you know what I mean?

FK: I almost hesitate to say this, because I don’t want to be like a grouchy old crusty fan—and please forgive me if I do—but I do think that within Supernatural there’s a thing like this going on where fans who watched the show in the context when it started, at the time, have an understanding of what the show is that is about that context and that time. Which is frankly a somewhat homophobic show that people are choosing to read into, because it’s this classic “here are these dudes who’ve crushed down any form of femininity so hard that they’ve come all the way back around the other side,” right?

And that’s a classic queer thing to do, right? That’s a classic reading. It’s the most classic, right? Dean is so butch and so in the closet, and so clearly not intended to be butch and in the closet by the writers [laughs] in those first seasons. So if you’re coming at it from that perspective, then later on you can sort of see all of this and be like “Yeah, wow, they’re baiting us. I like it, I’m being baited.”

But if you came in later on, the show changes a fair bit in that run, and also so does the world around us, right? It becomes conceivable, if you’re watching TV and you just started watching Supernatural like five years ago, it’s totally number. The CW has a bunch of queer characters on the CW who are doing various things. I mean, obviously sometimes they die, like Lexa, which sucks, but there’s also a bunch of other ones who don’t, right? You can totally expect that this is gonna go a different way.

So I think that there’s some amount of context and so on that leads you to either see this as “Oh, obviously they’re baiting us,” or “I cannot bear to think that they’re baiting us.”

ELM: Right. I, I think that it’s also fair to say that I’m sure that there’s some fans who’ve been there the whole time who’ve thought about that changing landscape and said, “Why the fuck—”

FK: “—not change too,” yeah.

ELM: “—should this show play by the rules of 15 years ago.” I think it’s worth talking about the landscape of television at that time though because like, this is one of the things that’s actually really helped me understand, as I have over the past five years collaborated with you and reported on stuff and learned more and more about how industry-side stuff works, I have come to a better understanding of like, what a lot of these writers are thinking, especially back in the day. Like, in the ’90s, in the 2000s in particular.

FK: Right.

ELM: This kind of idea—which floored me when I learned this, because I’d been in fandom for so long, assuming like…I remember there’s an early episode we did called “The Powers That Be,” and I was operating from I think a traditional fan perspective of assuming there was like, shadowy network executives who were like “NO GAY! You made this gay? No! I’m not airing it!” You know? And like—it’s not that cartoonish. I don’t wanna insult cartoons. [laughter] It’s not that reductive, you know?

But also, like, I’ve had conversations with TV writers from that era talking about, you know, working on shows that had big queer ships, like male/male ships, and saying like, “Oh, yeah, we had them,” you know, “doing like—staring at each other, that was a gift to the shippers!”

FK: Yeah!

ELM: And I was like, “That’s not a gift! That’s kinda mean!” Right? To me, even, even thinking about like, myself in 2005, if I had known that was what some people were thinking…I don’t know. That just feels like, that feels literally like baiting, right? And that doesn’t feel, that doesn’t feel like a kindness to me. That feels like a tease, because it seems like a fundamental misunderstanding of what shipping is. It’s not just “I like the look of them together.” But it’s a lot of times for me, I don’t like the idea of it being mocked in that way. And that can feel a bit mocking, even though I know some of these writers don’t mean it that way. But some of them do it in kind of an “I’ll throw them a bone” sort of way. You know what I mean?

FK: Yeah, sure! I think that the thing is though that that was an attitude that people who were even active in slash shipping had, right? I mean, there were shows that had people who were active slashers—

ELM: Yeah, sure.

FK: —who were writing for the shows. They were not public about the fact that they were writing fanfiction necessarily at the time, and those people stated those feelings as well. They said “Oh yeah, we’re doing this because…”

You know, I think it’s also different for same-sex ships in a context where you know that there will never be any consummation of that. And I do think that most viewers who were into a slash ship in the ’90s, certainly, knew that they were reading against the text. This was a conscious, intentional thing, and there was never going to be—that text was never going to do more than be sort of campy wink-wink nudge-nudge, look at how naked they are together, but it’s totally non-sexual. You know? [laughs]

ELM: Right, right.

FK: So I think that was a bit of a different feeling, and by comparison, I think, if you were into a het ship, that felt a lot less nice [laughs] at the time. Because there is an idea that those people can get together.

ELM: Yeah, I guess I—my trouble with the 2000s is like, that coming of age in that decade and remembering it very well…I feel like in some ways a lot of TV writers were like, lagging a bit behind the times.

FK: Yes, agreed.

ELM: If you think about shows coming out in the mid-2000s, and I know there’s an interesting—I’ve seen some interesting commentary around Supernatural too saying, “Yeah, I get it, I know there’s queer characters on other shows, but I wanted this kind of show to have queer—I wanted this kind of ship to actually happen,” and I absolutely understand that argument. And I feel like that’s one of the things I love about fanfiction because I have this, like, resignation that I don’t actually think—in the big superhero movies—there’s gonna be tender deep romance. So I can have those two things happen at the same time.

FK: So you mean you want like a long, slow, will-they-or-won’t-they, classic TV show…

ELM: No, I mean I’m even thinking about tonally, but I have seen that argument as well, right. I can see, “Oh, I want in my campy—” but whatever, there are also campy genre-y things, like Legends of Tomorrow or something like that, that are coming out now, that have tons of queer characters. It’s not all prestige dramas.

But then I also think, “Well, long before Supernatural came on the air, Willow and Tara did magic spells together,” so it’s not like there were never gay characters in this kind of genre stuff on the same network, by the way. You know? Like, I understand that element of it coming from a ship, right? Like, Tara was introduced as the burgeoning love interest of Willow. It wasn’t like Willow and Buffy got together.

FK: Right.

ELM: Tara was introduced in just the way that Riley was introduced. You were like, “All right, yeah, I get it, that’s gonna be Buffy’s next boyfriend,” right? [FK laughs] And with Tara you were like “Wait, is that—is that gonna be Willow’s next…” You know? I’m making, like, a…

FK: A very speculative face.

ELM: Like “Yeah? Yeah? Are they gonna have…” Y’know? Right? So it’s like, in a way that’s not the same thing as—I totally get the kind of, like, you want it to be like Mulder and Scully, right? You want them to be like, “OH! Those two! For so long! So many cases!” [FK laughs] “Surely they see the same thing I see! Surely they’re doing it on purpose.” Right? I absolutely understand that.

FK: Yeah.

ELM: But I just think it’s so hard because it just feels like such a holdover of this particular era of television, you know?

FK: I think that’s absolutely true. I think that’s absolutely true. I think that people were lagging behind and I think they still are lagging behind to some degree, frankly, in terms of what specifically, like, the queer-ship-interested viewer expects and wants. You know?

ELM: Yeah, you say that but when you think about the other big ships…I don’t know, it’s really hard because it’s often apples-to-oranges too. Because like I said, I don’t think—I think when Marvel has a gay protagonist, it’s going to be very deliberate. It’s not going to be—

FK: Yeah.

ELM: —that person who’s been here for the last six movies and makes a lot of eye contact with that other guy. That’s not the way they’re gonna do it. They’re gonna be like, “Look at the first gay superhero!” You know? And they’re gonna make a big deal about it. They’re not gonna spring it on you as some sort of secret message, because it’s such a deliberate, carefully orchestrated mass media.

FK: Right, but I think that then that idea of careful orchestration is something that people know exists, and then want to be carefully orchestrated for their thing.

ELM: Right.

FK: “I know that Marvel is carefully orchestrated, and I really want them to be carefully orchestrating the thing that I want.” And usually they aren’t, you know? Unfortunately.

ELM: Yeah, absolutely. I don’t know. It’s tricky, this is such a big conversation and I feel like there’s so many different angles to go into it. But you know, one thing I think that we should do—because I’m conscious of the time—is we got a couple of other letters that I think are work discussing, that are related to this, because both of these letters—not to give them away in advance—but they’re about audiences, and I think that is one thing that I have been really thinking a lot about as I think about this queerbaiting conversation. This kind of idea of who is this show for? Who are these shows for? Who’s making them and who do they think they’re making them for? I think there’s so many mismatches, and that’s—it often sucks.

FK: Right.

ELM: To just say, like, “Oh this show isn’t—they’re not thinking about what you want when they make it.” That sucks. And like, maybe on them! This is a hypothetical “them,” maybe I’m talking about Sherlock right now. What are people supposed to do with that? What are queer fans supposed to do with that? So I don’t know. But anyway, we should read them before we run out of time. Let’s discuss them a little bit.

FK: OK. The first letter’s from Nicholas.

“Hey Flourish and Elizabeth, one, I hope you are all doing well after Supernatural has ended. I am still processing.

“Two, I came across this article—” and it is the Supernatural finale recap that Aja Romano wrote. “Something stood out to me. Quote:

“‘It took a long time for the show itself to acknowledge its own core demographics, though. Throughout the series’s early and middle seasons, the writers consistently seemed to be writing for (and in some instances about) an imaginary audience of mostly male viewers. The show catered to the idea that Supernatural fans were akin to archetypal superhero or comic-book fans, geeky men driven by fantasies of becoming the hunky Winchester bros, rather than geeky women (and queer people) driven by fantasies of—well, you can fill in your own blanks.’

“While I agree with the claim that Supernatural’s hardcore fans are women and LGBTQ people, I’ve never seen any data to confirm this. Have you come across any data about Supernatural's demographics?”

ELM: OK. So I asked you to do this, because…

FK: Yeah, yeah yeah.

ELM: You work in the television industry or whatever. But like, we couldn’t find as much information as we wanted as we researched this.

FK: Yeah. So I will say, what Aja’s saying seems to be correct, in that in the early episodes there’s literally—they reflect fans on screen, and the fans they reflect are male and in those ways. And then later on, you know, it sort of shifts.

We were not, I wasn’t able to find any actually I would say “authoritative” data about the gender breakdown of Supernatural viewers. The Supernatural fandom, meaning the people who, like, show up at conventions and talk online and so on, I’ve seen a bunch of figures thrown around. People have said 80/20 for Supernatural fan cons…there’s been lots of stuff tossed around. But I think people generally agree that that loud viewership, the talking viewership is mostly not men.

I also saw a bunch of people saying things like, “The overall audience is 60/40 women/men,” which is normal for TV, that’s the normal TV viewership split—and of course that doesn’t take into account nonbinary people, because the entertainment industry usually doesn’t—but I wasn’t able to find anything to actually say that.

What I was able to find was sort of numbers about Supernatural’s ratings, and also information about sort of where it’s popular. So one of the interesting things is that Supernatural is popular about the same amount all across the United States. Most shows are either shows that people watch in cities or in the country, but Supernatural, everybody in the U.S. watches it about the same amount.

ELM: So wait, I think that the data that’s from is the, like, incredibly fascinating research that was published in the Times, and it was like the most popular stuff amongst Republicans—some of it, people I know were like “I’ve never heard of that.” It was like, you know that show where they kind of orchestrate—it’s like Cops but worse? You know that show?

FK: Yes. [both laugh Yeah! So I’ve actually seen this data, you’re right that the published data is New York Times data, that’s where that comes from. But I’ve also seen this within internal industry studies, which were about people who self-identify as fans of things. And I can’t cite that because it was not something that is, you know, up for everyone to access online. But that’s a second point of data that I promise you is a real study that happened. [laughs] You know.

ELM: So, but the point is that—well, we don’t know about political leanings, but we do know that in terms of like, geography…

FK: Right.

ELM: Supernatural is very popular in rural areas as well as urban ones, which is very interesting, cause there are very few shows that actually bridge that divide.

FK: Almost none, almost none. So then the other thing that we know about is we know about the overall number of people who watch Supernatural now and watched Supernatural in the past. And so, when Supernatural first came on, about five million people watched it, in the first season.

ELM: Per episode.

FK: Per episode. The final episode had the highest viewership for the past two seasons, with 1.4 million viewers. So there was some fall-off, but actually I don’t know how much to like, adjust that, because all television ratings—like, all numbers of people watching TV have fallen off in those 15 years, because there’s just more streaming, there’s more stuff available. So fewer people watch any one thing, right?

ELM: Right, right. So you probably got a lot more casual viewers of the show early on, just because they had the CW and they didn’t have a lot of choices.

FK: That’s exactly it. And we see this across everything, right? Like, the numbers today that support television shows are incredibly tiny. Like, Twin Peaks had a much larger viewership than Supernatural when it was on the air in the late ’80s, early ’90s, and yet it was a total failure that no one watched, even though it was a cultural phenomenon, and got canceled.

ELM: Right.

FK: The other thing I should say though is that, you know, you might not—if you don’t know what TV ratings are like, you might not know how many people watched other shows. So to give some context, the Game of Thrones finale had 19.3 million viewers. So it’s many, many times the amount of the Supernatural finale.

ELM: And this is in the United States.

FK: Yeah, this is in the United States. This is just Nielsen ratings. And then if you wanna look globally about something that’s truly a big global franchise, Avengers: Endgame sold 93 million tickets. You’re probably used to hearing about that billions number, but the actual number of tickets, 93 million. So even if you assume every viewer saw it twice…

ELM: I saw it once, so, uh.

FK: Someone saw it 30 times, don’t worry.

ELM: Yeah yeah, balance me out.

FK: But yeah, even if you assume that every viewer saw it twice, that is also much bigger than Game of Thrones, right?

ELM: Right, right.

FK: So this is how these things go. And for some other context, the original Star Wars film is one of the highest ticket sales of any movie with 178 million tickets. So I think it’s number two.

ELM: Interesting. Is that just in 1977 or does that include the re-release in the ’90s, do you know?

FK: I’m not sure, actually.

ELM: When I saw it in theaters.

FK: When I saw it in theaters, too! I think it might, but I’m not positive.

ELM: Interesting.

FK: I would need to look that up. But regardless, that’s still a lot of tickets, so…

ELM: Yes.

FK: We’re really talking, I think this is something that gets lost, because in fan culture, like, we look at like, who—this is, this is part of why I talk about Supernatural punching above its weight class, right? Is that truly, when the conversation about Supernatural is so large for so few people [laughs] that’s wild. I’m always using it as an example in my work of: this is a show that is truly the little show with the big voice.

ELM: Yeah, yeah. So we have a second letter, kind of by chance, I think, they sort of speak to each other. Because having to actually look at the numbers…it’s interesting for me to hear, because I do feel like Supernatural feels…it’s interesting to see the huge variety of responses, and it’s also interesting to see—that’s one of the things that I am very interested in as a journalist, always, is kind of looking at the range of responses and trying to parse out, like: what are fan responses and what are general audience responses, and what are media responses and all of this stuff, right?

And like, you know, unlike some other stuff where we’ve seen a lot of controversy about queerbaiting or about a ship not becoming canon, I feel like so much of this falls just within the fandom, as opposed to—like, honestly as opposed to Sherlock, which had something like ⅓ of all households in Britain watched Sherlock at one point, right?

FK: Yep, absolutely.

ELM: Everyone and their British grandmother, every British person and their grandmother, had an opinion about it. And you were kind of battling public opinion. And I think that adds another kind of level of it, too. Like, this sort of idea of “what are the public reactions to it?” And so this kind of ties in nicely to our second letter. So do you want me to read that one?

FK: Sure, go for it.

ELM: OK. So we got this on our website, shortly after the finale aired. Subject: “Men and their feelings on screen.” Message:

“Hi Elizabeth and Flourish! Long-time listener, first-time communicator. In the, uh, rather scorched-earth aftermath of a certain long-running show’s finale this week, I was struck by the backlash to several episodes where we see the male lead characters laid emotionally bare and vulnerable, and openly voicing their feelings. I was reminded of some of the backlash, from some of the same channels, to Avengers: Endgame (and Marvel tentpoles generally) where the main criticism, rightfully, was that there wasn’t enough of this masculine vulnerability. Is this a ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’ situation? Could ‘ship wars’ serve as an excuse for mainstream media to avoid exploring loving male/male relationships, especially when those relationships are not easily classified as romantic?

“Thanks, and wow 2020 is the worst, Liz.”

FK: All right, well, I have to admit that I’m not totally sure which channels are saying these things entirely. Liz, you did too good of a job of talking around some of this stuff, because I was like, “Which, where was this backlash coming from? Was it to the—” I’m not sure. But! I will say that I think that, I think there is sort of this question, yeah, of—you know, I mean, is it even the framing of “excuse,” like, when there are different audiences watching a show, you know, does that mean that people end up taking sort of a lukewarm path, and not pleasing anybody?

ELM: Yeah.

FK: So one of the interpretations of what’s going on in the Supernatural finale is that the writers were trying to make everybody happy. If you want to imagine that Dean and Castiel meet up in Heaven and have a loving life together, you can imagine that. There’s nothing that prevents you. If you want to pretend it never happened and Castiel’s love-confession to Dean was just a blip, you can also pretend that.

ELM: They could still be in Heaven together and just not, just bros!”

FK: Because it’s Heaven, Dean could be like “No, bro,” and Castiel would be like “All right, bro, well, it’s Heaven, so I guess it’s OK,” and they could just bro off into the sunset together, right? So I think, like, obviously that—that’s an ending that pleases nobody, but I can see that, you know, you could try and chart your course there, right?

ELM: Absolutely, but that is a little bit different than…bringing up these numbers and talking about the diversity of audiences or whatever, when I think about Marvel, and I think sometimes in fandom we can tend to flatten things a little bit? Because it’s all just another fandom in the AO3, you know? Alongside, like…

FK: [laughs] Right.

ELM: Some random fandom that’s like, super-popular in like, AO3 fandom only, and not actually, you know. Like Inception fandom or whatever, right? As a fandom, you know what I mean. But Marvel, close to 100 million tickets sold for that last movie—huge, huge diversity of audiences there, you know? And frankly, I’m sure listeners know, I’m not a massive Marvel fan, and I often feel like these are films that kind of get whittled into something by committee, you know. Something very, you know, kinda straight down the middle. And I absolutely understand people, like, they emotionally resonate with people. They don’t really work for me in that regard, because they often feel like they’re not saying much at all.

But in that way, it lets people kind of latch on to what works for them. So if you love teams or you love explosions, or you love, you know, Steve and Bucky looking at each other, there is something there for you. Maybe not enough. I’m sure there’s some explosion fans who wish it was all explosions and no talking, you know? They might be like, “There’s too much talking in those movies. I wish it was two-and-a-half hours of boom,” right? [FK laughs] I don’t know if those people exist, but you know what I mean?

FK: Yeah, totally.

ELM: So like, I feel like that’s a deeply unsatisfying answer regardless of what piece of media we’re talking about, to say “Oh, they were just walking down the middl eof the road there. Don’t you worry about it. You take what you need from that.” It’s like, well, what I need is actually something substantive that feels deliberate and fees—

FK: Right.

ELM: —not like they’re catering to you, but feels like they actually committed to something, you know?

FK: Right, but at the same time I mean: that’s capitalism, baby! You know?

ELM: Wow, wow.

FK: I always think about—people used to say “Yeah, but will it play in Peoria,” meaning you make a television show in Los Angeles but it has to speak to somebody who’s living in Peoria with a totally—at the time, totally different culture, totally different expectations about everything, right? Something needs to be, to speak to everybody in the United States.

And number one, isn’t it ironic that Supernatural is one of the very few shows that actually does play in both Los Angeles and Peoria, and number two, with things like these movies, it’s not “will it play in Peoria,” it’s “will it play in Indonesia? Will it play in Russia? Will it play in the U.K.? Will it play in Brazil?” Will it play all these places. Will it be not culturally offensive in any of these places to the majority of people. Will it pass through the Chinese censors and get played in China.

All of these questions are really—I mean, they are necessary. It’s not just like it would be nice to have, but if you’re making something that has the budget of Avengers: Endgame, it has to play in all those markets, you know? So that’s capitalism and that sucks, and that’s why maybe, you know, it’s nice sometimes to look at things that are smaller projects that have lower budgets that can therefore be, you know, targeted to a particular audience and not try and be everything to all people.

ELM: Yeah, absolutely. And again, I think that brings you back to “Well, I want this to be the thing for me, but also this thing.”

FK: Yeah, which is fair! I want that too!

ELM: I can be like “Well why don’t you just watch Portrait of a Lady on Fire, that’s about actual,” you know, “actual queer people having sex on screen! And it’s beautiful!” And that’s useless. If I want whatever, if I was deeply invested in my X-Men ship becoming canon, me telling other-me “watch this French lesbian movie set in the 18th century” is not helpful, you know?

FK: Does not solve the problem.

ELM: Right?

FK: But your problem may also be insoluble, honestly.

ELM: Yeah.

FK: And this is one of the things that’s rough, too, is that I think sometimes problems are insoluble. Like, sometimes we don’t get what we want because we cannot get what we want, and it fucking sucks.

ELM: Yeah, OK. Let’s circle back a little bit as we’re winding up. I wanna go back to the baiting element.

FK: All right.

ELM: Cause this is about queerbaiting, ostensibly.

FK: Yeah!

ELM: So there are a few things I think about when I think about queerbaiting, but one of the things I’ve been really struggling with over the last few weeks—and I’ve definitely had this with other ships too, including ones that I have participated in—where I think there’s often a conflation of representation with shipping, and as we’ve talked about 8,000 times on this podcast, those two things are not equivalent.

FK: Nope.

ELM: And the ship kind of getting in the way of people being able to talk about queer representation and queer media, because I think it’s absolutely possible to care both about queer representation and care about your ship and care about your ship because it’s a queer ship.

FK: Yeah.

ELM: Without those things being directly equal to each other. You know? In terms of like, you know, one-to-one swap. Those are like, those are different strands to me. I think they get conflated constantly in fandom, and it is a point of frustration. But like, this is one thing that I’ve been struggling with, watching some of the responses to this, because I don’t know. At some point it starts to feel a little mutually exclusive. If it is canon, isn’t it an insta-Bury-Your-Gays, you know?

FK: It is!

ELM: Or…I mean, I did see, I saw someone arguing—and I do agree with this—I think that the “Bury Your Gays” trope can be a little abused and a little broadly applied. Like…it also potentially could be read as like a, you know, a great central queer character—a queer character who’s central to the story sacrificing himself, right, in the way that Buffy sacrificed herself, you know what I mean?

FK: It’s not, all Bury Your Gays are not created equal, and this is not a senseless Bury Your Gays, I will give it that. It was instant, to the moment it becomes stated as canon. But if you really believe that Castiel has been written as queer for the whole time—and I think that there’s some pretty good arguments that the actor was acting him as queer; he’s said plenty of times that he was doing that, you know what I mean. So if you really believe that, and you believe thatall those tracks have been laid, then it was a great act of self-sacrifice, the gays were not buried for a long time and when they were buried they were buried for a good reason—and then, offscreen, but he gets to be in Heaven. So that’s not the greatest, but he’s also not perma-dead.

ELM: Absolutely. But so when you start to—but then you start to, like, quibble over, “Well, what is his exact fate?”

FK: Right. [laughs]

ELM: And it’s just like, well, wouldn’t it—wouldn’t it have been cooler if in fact you hadn’t had to, like, you know, pull up the microscope and try to look at the—the split hairs to—

FK: Much. Oh, it would’ve been!

ELM: And it’s one thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about, and I think that there’s a lot of different interpretations and I’m truly saying this just as an observer, but I am partly speaking from the experience of watching interpretations of Sherlock, a text that I know intimately and have seen the episodes of a million times and read all the fanfiction and stuff—not the fourth season, I watched that once and one time only, I want to make sure is on the record. [FK laughs]

But some of—I have been thinking over the last week or two about some of what I thought was kind of bizarre discourse about Yuri!!! On Ice. Where, if anyone hasn’t seen it, about halfway through the two protagonists, who you think are interested in each other, have an extremely dramatic kiss that involves one of them like, landing on the other one on the ice skating rink after, like, the triumphant incredible performance, right?

FK: Like a full-body, like, flattening-level…

ELM: It’s extremely romantic, right? I love hugging my friends, but I’ve never hugged a friend so they fall on the ground that way. But because of the way they animated it, you literally don’t see their animated lips kiss, because, like, a hand is in front of the other one. And in fact, you never see their animated lips kiss. But from that point on—this is huge spoilers, but I think it’s been long enough that everyone has seen Yuri!!! On Ice at this point, like—they are boyfriends being extremely romantic together!

FK: Yes.

ELM: Right? And there was a strand of discourse, which I found baffling, about whether it counted or not. And I was like, I—all right, I absolutely understand that like, why it might have been cool. I am not a big anime watcher, and if you, if everyone is telling me that male/female couples in anime do a lot of on-screen kissing, sure.

FK: Yeah.

ELM: But beyond that, when I look at it in the context of the story, I’m like, “What on Earth? This is extremely deliberate and romantic.” This isn’t like, there’s no way to argue that they are not a couple now, a plain old romantic couple with no ambiguity about it, right? So then I start to think about, like, take Supernatural out of it: I start to think about Sherlock and it’s like, if they had said like, “I love you, Sherlock, I love you, John,” at the end, that doesn’t change the rest of the show for me. Which is I think about a romantic relationship of two people who are not in a—you know what I mean? I find their relationship plenty romantic, but it’s not like it was some secret, you know what I mean?

Because the context matters to me. I don’t understand this kind of binary on/off stamp of like, “It counts, so now everything before it counts.” That kind of sense kind of tends to completely disregard the actual context and the things that you’re seeing, because it’s like, maybe this is a tortured metaphor, but it’s sort of like you’re arguing over whether you got like a first down, and your team is still like, way behind, and you’ll never—you know what I mean? Is that too weird a, to bring in a football metaphor?

FK: That’s a weird sports metaphor, no one’s gonna know what that means. [laughs]

ELM: Everyone who knows what football is is going to know what that means.

FK: I know what that means, but there’s gonna be a lot of our listeners who do not know what that is. The downs, downs are really confusing to people who don’t watch football.

ELM: No, it’s the most straightforward part of football! It gives it meaning!

FK: You have tried to—I mean, come on, I know you’ve tried to explain this to people before, and I have, and they never get it.

ELM: All right, if anyone wants to explain the basic rules of football, I am here for you.

FK: Anyway, I think that you’re right that there is this element of like—it has to be this kind of explicitness and then that puts a stamp on the past. But I think there’s something else going on here, which is I kind of wonder sometimes—are we at a point in fandom where you can’t just want something to happen because you want it? Like, I would like to see, you know, I would really like to see these two characters kiss, because I want to see that come into my eye holes and enter my brain. I want that to happen on screen. I think it’s hard for some people to say, “I just want that, and it’s not because of a political reason or a social reason or anything else. It’s just because I want that.”

And I think that’s really hard for a lot of people to say. I think a lot of people really want whatever they want to have, like, some noble purpose.

ELM: Well, I think that is true for some people, but I also think there’s another large subset of people for whom it is not necessarily… Like, I absolutely think that’s true, and I think that we’ve discussed this on the podcast before: I think sometimes especially female fans will use, kind of, the serious political argument around their ship, to deflect from a desire element—

FK: Yeah!

ELM: —and just say, “This is fun and I like it,” or “This is pleasurable to me and I like it,” that that’s not something that’s ever worth, ever worth anyone’s time, you know, because et cetera. I also think there’s a huge subset of people, regardless of whether they overlay a serious political argument over it, want to be right.

FK: True. It’s a powerful, powerful motivating force in all our lives.

ELM: You know? I don’t, I’m very wary of drawing broad comparisons between non-fandom-related belief systems and conspiracy theories happening right now, but like, in many countries around the world—not just ours—you have people operating on quote-unquote “different sets of facts,” right? And that butting up against reality. You know? And like, I think the tricky thing with fictional media is, there’s a couple different truths involved, right? There’s the like, humans who wrote it and acted it, and then there’s the truth of interpretation.

I don’t think this is new to fandom. I think it’s newer to queer ships in fandom. People were at each other’s throats in the Harry Potter fandom about which dude Hermione was going to wind up with, right? And they were looking for truth! They were like, “I’m reading this the right way.” I know some people were arguing it from a like, “She should go for this dude, because this one’s a clown,” which could apply to either of them. But obviously some people were saying “I’ve read these books correctly and I am pretty sure we are being told…” In the same way I felt that I was reading it correctly when I, like, read Dumbledore’s words and I was like “I’m pretty sure I understand where this is going because I read it correctly,” right. And I was looking for validation, and of course I had no idea what was going to happen, because there weren’t that many clues, you know?

And so like, I think that there’s a huge amount of power in this kind of idea of your reading being validated. But like, your reading doesn’t always…fans are rarely working with all of the facts of the realities of the kind of back end of a show.

FK: Yeah.

ELM: And they’re just interpreting what they receive, or dribs and drabs of that back end. You know? And also, like, sometimes like, what you want and what you desire and what you strongly feel like you’re reading from, is not what they were intentionally putting down! And I think that’s where the baiting comes in. It’s like—is it subtext? Or are they baiting deliberately? Or are they giving me clues that are leading to a big reveal?

FK: Right.

ELM: And these things get so jumbled and sometimes I think people can’t even tell exactly which channel they’re in when they’re shipping, you know?

FK: And, and, it gets even more complicated, because it’s not like there is just one mind. It’s not like everybody mind-melds to become one thing when they write a television show. There’s different people involved in it. So there’s different people and actors who have different takes on what’s going on in it, and then that really easily tips over into like, “Someone’s being silenced! Someone’s being censored! Someone’s being—” Directly into conspiracy theory thinking, which I know we’re gonna go into more in a future episode.

But all sorts of stuff can happen in that space, and one possibility is also always that like—sometimes there are people who want to do something and it doesn’t happen. Maybe someone wanted to make, in Supernatural, the Impala bright red. And they argued for it! And like, it didn’t happen! You know what I mean?

ELM: That would be absurd. I haven’t seen this show, and that would be ridiculous.

FK: Right, but I mean, you know, you can imagine that there’s all sorts of ideas that get thrown out, right? So I don’t know. I think it’s just really complicated and it’s really hard for people to wrap their heads around the complexity of the real world, and it’s actually also as hard to wrap your head around the complexity of like, the way fiction gets made, especially something like this. Like, I can’t do it, and I work in this industry. [laughs] You know what I mean? So it’s hard. And we’re all just sort of trying to struggle and make meaning as we can.

ELM: It’s tricky. I have to wonder, I mean like, one of the things that I’ve thought over the years—you know, studying and writing about fandom—is the repeated invocation, when talking about queerbaiting, of Sherlock and Supernatural. And thinking, “When these shows finally go away, what does this conversation become?” And one thing I have noticed, as other shows have come into existence, is people using the term in ways that I feel like are a little more loosey-goosey.

FK: Mm-hmm?

ELM: Like, I think with Sherlock and Supernatural it’s fairly straightforward. I understand how those terms get used within those fandoms, and I understand why there’s an expectation of an outcome and a disappointment and a question of whether the writers were teasing them intentionally or not.

But I’ve also seen queerbaiting invoked in ships with queer characters, when one queer ship is made canon and another one isn’t. I’ve seen it just invoked in a “you didn’t make my queer ship canon” context in a way that doesn’t actually connect to anything else, right? And like, that’s a bit frustrating to me, because I actually think that this term has a kind of a specific definition, and there is a broader world of—most ships don’t become canon. And talk to any het shipper, you know, longtime het shipper, and they’re gonna let you know that plenty of times that doesn’t happen, and you can really like something…

FK: Yeah, or shitty ships become canon. God! [laughter] I still bear some grudges, Star Trek! Anyway, moving on.

ELM: But like, when I think about our shipping survey, I remember we got so many people who went out of their way to talk about how they weren’t one of those shippers who cared about whether something was canon or not. And I just thought that was fascinating, cause it’s like, people understand—I think that whether people can articulate it or not, I think so many people can see how some portion of fandom anyway has become hyper-focused on this sort of affirmational shipping fandom. Not “I ship because I like it,” or “I ship because the fanworks are cool and I wanna read and write in that group of people,” and not because “I like what I see on the screen,” but “because I think that I’m reading the text correctly and this is the outcome.”

And it just, so often to me it cheapens conversations about queer characters, it diminishes them. I don’t know. I just find it often very frustrating, and I love shipping, and I love my ships. But I just don’t think that, you know, turning it into this sort of yes/no thing, is it real, is it not real…based on, like, whether my specific vision for how it was all gonna play out was affirmed or not…I don’t know, it’s really hard for me to reconcile. And it was very hard for me to deal with in some fandoms that I’ve been in. And I don’t, you know, I have absolute sympathy for anyone in any fandom who feels like they’ve been misled.

FK: Yeah.

ELM: But I also just think it is—it’s a conversation that I, I wish fandom collectively could take a little bit of a step back from. And kind of reassess a little bit about like, I don’t know. I think it’s really hard. I think it’s hard for people to articulate. It’s hard to untangle your own feelings about why you want something and why you’re feeling something. So that’s a huge ask. You know what I mean?

FK: Yeah! Yeah. Yeah, and it’s, and it’s hard to unpick the things that are freighted with meaning around queer ships as opposed to around het ships, you know. It’s easy to say “Oh yes, it’s very different, between those two things,” but then it’s hard when you look at your own feelings about those things to fully unpick all of the pieces within that, I think. For me it is, anyway. To really, you know, to really say “Why is it that I have this emotional reaction here and this one here, and how does it—” I don’t know, man! This is rough.

You know what I can say about all of this? We should all be kind to each other as we’re trying to figure this out, and not be jerks to each other.

ELM: Cool. That’s a good takeaway.

FK: I think that’s like—genuinely, I think that’s the best takeaway we can get here! [laughs] Don’t be jerks!

ELM: Yeah!

FK: No matter if you think you’re really right, wherever you’re at, try not to be jerks to people! Because I see a lot of people being jerks right now, in a lot of different directions.

ELM: I do too.