Alternate Universes

Through text-based roleplaying, I’ve lived so many other lives—and experienced so many other bodies.

by Newt Albiston

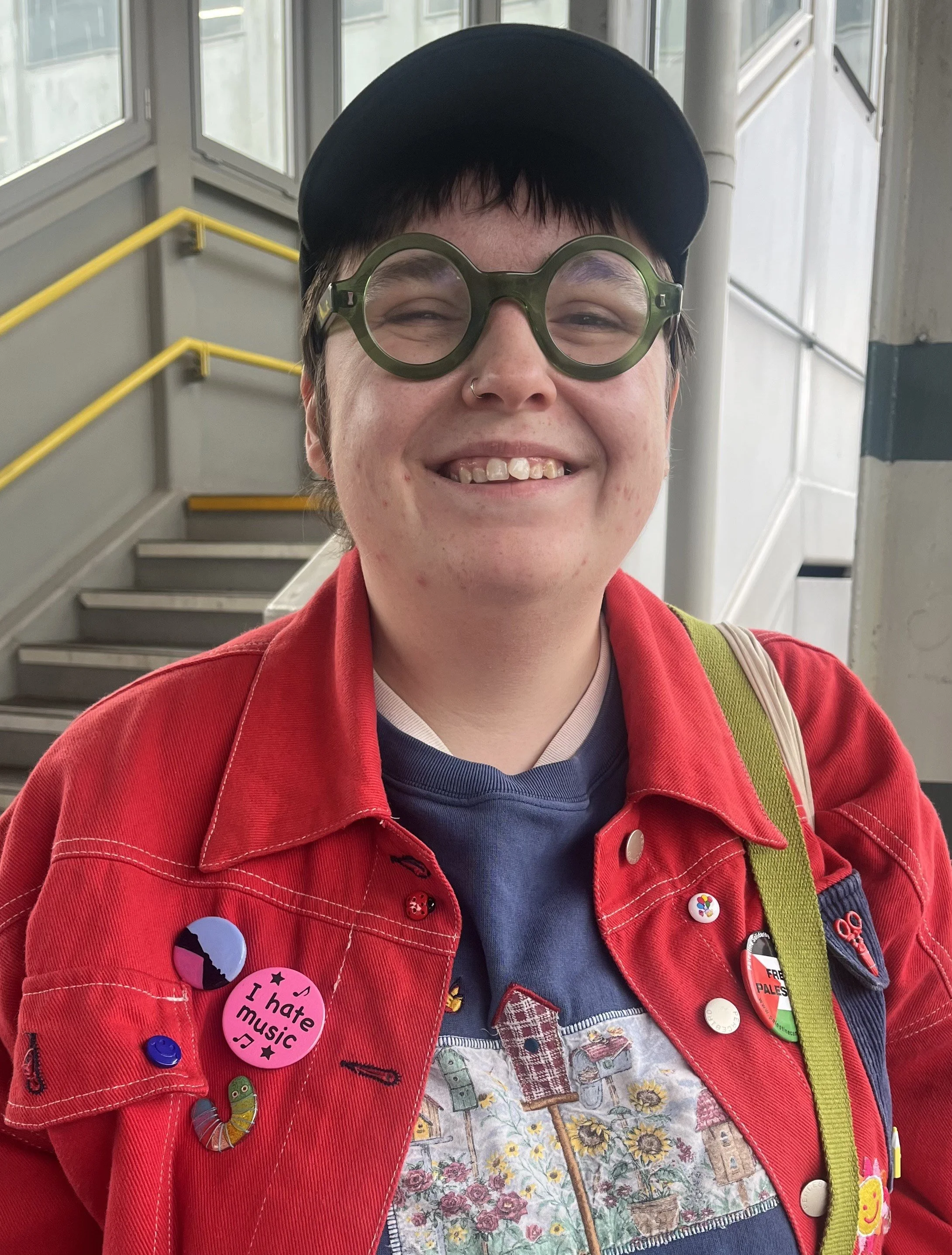

Illustration by Anna Lark

This article is brought to you by Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more writing like this in the future, please consider becoming a monthly patron or making a one-off donation!

I’m 14 years old. I live just outside of London with my dad and my sister, and I’m the only openly queer person at my secondary school. Under bed covers at 2 A.M., I’m using a poorly made website to talk to strangers on the internet.

These people live on all corners of the planet, and we share an innate enthusiasm for twisting and shifting the already fictional lives of fictional people. They all know me by a different name—and no one thinks I’m the girl that my family thinks I am.

The practice is called text-based roleplaying, and I’ve been doing it since I was 11, starting out on an equally poorly made app that my mum and dad did not approve of before purchase. It was essentially a virtual high school, with no pictures but multiple forums full of strangers to fight with. The chat feature was as rudimentary as you could get.

I met my first girlfriend on that app. We were in very different geographical places, but that didn’t matter. We would virtually play house, but as members of the band My Chemical Romance. I was always Gerard and she was always Frank. I didn’t stop to think about why I always preferred pretending to be men and boys.

We were their partners, but we also controlled them. Under our thumbs, they could be anything we wanted—but they were mostly just excellent boyfriends. I don’t remember much of the content of these stories, but I know we spent a lot of time pretending to virtually kiss through these characters.

That relationship lasted for 3 months, but the habit I formed there has continued throughout my entire adult life—it would even end up shaping it. From my adolescence to my gender transition to my broader interest in fandom culture, text-based roleplaying has been at the heart of it.

You know what fanfiction is. You could probably even describe it in layman's terms if you had to. It has unequivocally escaped the confines of fandom, and now has a rich life of mockery and concern in the hands of people like your co-worker, your mum, or a major publishing house. Fanfiction is now baked into our cultural lexicon, and even the lexicon of the media we create about the past.

What you might know less about is her often misunderstood cousin. Text-based roleplaying, or simply ‘roleplaying,’ is comparable to fanfiction in that they both stem from the desire to expand the narrative of a pre-existing world. Where roleplaying differs is it’s a much more interactive medium. It can be conducted by two people, or twenty; it can last an afternoon, or a whole decade.

Some of my initial dalliances with roleplaying were on Tumblr, where custom blogs for an ark’s worth of characters still thrive today. The most prevalent forms of roleplaying are in private or public chat clients like Discord, Messenger, or previously, Kik. In public forums, you might be responding to someone else’s post in-character; private chats might take the form of detailed paragraphs, known as paras for short. In plain terms, text-based roleplaying is the act of communal storytelling, conducted on various internet platforms.

A less linear expression of fan excitement than simple fan-to-content interaction, text-based roleplay has been happening on countless platforms for probably as long as fanfiction has—and often lives in the same emotional domain of desire-filling, of self-satisfaction and indulgence. Think playing house with your friends at school, but on an arguably more expansive scale. Think young girls pretending to be members of their favourite bands and ‘kissing’ as if they were (like, for example, the girls pretending to be those mop-topped Liverpudlians from the 1960s, as described in Allegra Rosenberg’s “The Beatles Live!”)

Although it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact moment that text-based roleplaying emerged into cult consciousness, the origins seem to have roots in the late 60s and early 70s. At the time, most roleplayers were using newfound computing systems to roleplay extended scenarios related to the now beloved table-top game, Dungeons & Dragons, or D&D.

A turn-based game that people play in an attempt to connect with the ever-prevalent need to have control over a five-person friendship group (or possibly because they just really love the fantasy genre, but maybe there’s no difference), D&D and text-based roleplaying seem to share much of their DNA. They’re both rooted in the art of telling stories, especially with friends. Much like fandom roleplaying, D&D and games like it are examples of taking pre-existing stories and elaborating on them further with other people.

For myself, this kind of collective storytelling was something I was keen on (as an avid childhood ‘house’ player), and something I would only become more obsessed with as the years rolled on.

My personal journey with roleplaying has nothing to do with D&D. Engaging in fandom was something I started doing the second I found out that people could form proper communities around the things that they really liked. Andrew Hussie’s mammoth webcomic Homestuck, about a boy and a host of his friends playing a mysterious game, was my second roleplaying muse, and I would play all day long.

I’d use a private tab on my secondary school’s iPads to answer my roleplay partners in the middle of math. I’d sneak texts under the table, and stay up into the wee hours of the morning forming a domestic universe around my favorite ships and characters. I spent years honing my universes and arguing with countless roleplayers about the validity of each other’s portrayals, shit that never ended up mattering in the real world. Wasn’t it nice to have felt such big things about stuff that most other people would find inconsequential?

The stories my countless internet strangers and I would write focused on identity, character study, and the art of feeling scary things out loud. It was putting on a new costume for the day, and assuming a new life. Sometimes they were zombie hunters, sometimes they were just humans living in a flat together, sometimes they were the canon versions of the characters. Emulating other fans and whoever I’d be reading at the time (usually fanfiction, always fanfiction), writing text-based roleplays were always miniature experiments. For example:

“It could sometimes look like this!” He typed on his barely-functioning computer.

Newt: Or it could look like this! *He smiles, waving at you from across the screen.*

Over the years, the hobby has gone from a fierce stakeholder in my daily functioning to a leisurely practice I use to sharpen my writing skills. It’s an unexplainable practice to most people. There’s simultaneous nuance and simplicity in someone’s choice to use roleplay as their primary storytelling tool. Sharing stories is a human quality that we all have the capacity for, and arguably, a practice everyone partakes in in some way. Creating miniature universes in code and text? That was my way.

It wasn’t until I shifted into early adulthood that I realised the journeys my roleplays were taking me on were not just pure fun or fantasy—not just storytelling for the sake of storytelling. I was living inside of my characters, and using them to make sense of my world. I was growing more and more curious about my gender identity, and so were the contents of my roleplaying.

In his 1988 essay “Therapy is Fantasy: Roleplaying, Healing and the Construction of Symbolic Order,” John Hughes set out to understand the character creation critical to all forms of roleplaying, and the projection that a player can use to feel closer to their character and their own reality. “Compensating Symbols are characters created to explore a characteristic or skill that the player believes they do not possess,” he writes. “Shy players attempt to play forward, confident characters, cerebral bookworms create bare chested barbarians, impatient players create silent, meditative monks.”

“Compensatory characters,” as he dubs them, are a major part of what makes roleplaying such a personal and intimate act. The case study he explores is a young woman using roleplaying to understand and fight her depression. I can’t think of anyone I’ve roleplayed with who hasn’t used roleplaying as a way to escape reality, or even trial a new life. Some people go to therapy, and some people write with their friends about semi-fictional pirates having sex. Some people do both!

Overcompensation is, in my eyes, a crucial part of the young transgender experience, and experimenting is the close friend of such an act. It makes sense to me now that I was using roleplaying as a form of gender therapy, but I wouldn’t realize it until I was around 18, as I started to write about my hopes and fears for my young trans body with my roleplaying partners. I probably wouldn’t have ever understood that I was a trans person if not for my chronic habit of roleplaying men.

I often found myself asking one of my oldest roleplay partners if she wanted to create a scene out of typically gender-affirming activities. The recovery period after top-surgery, a trans man’s first-ever injection of testosterone. A naive part of me thought they would just be fun topics to write about, that I’d see them as fantastical as if we were writing actual fairy stories—but the more I asked, the more I was validated. And the more my roleplay partner silently gave me the green light to explore, the more I wondered what it would be like to have as much acceptance as my virtual counterparts were given.

I wasn’t alone in my desperate folly to make sense of myself. When starting to write this essay, I racked my brain to remember if anyone I’d roleplayed with was cisgender. There had to be someone who was cis, someone who didn’t use roleplay as Transsexual Simulator 3000. It was not an easy feat. Upon reflection, I remembered times where I’d be in a Discord server with 20 other roleplayers, and every single one of them would be somewhere on the trans spectrum. It was easy to forget that cisgender folk even existed in that world.

In my alternate universe, one of many alternate universes, my body is slender but strong. My chest is flat and my tattoos are marvellous. 2 A.M. on a Tuesday morning, Discord’s automatic dark mode doing little to light up my eager face, the alternate universe version of myself is a cowboy, a sailor, a professional chef. He’s got a gruff voice and has plenty of graphic sex with anyone he wants to have sex with, because he’s flat and marvellous and a man. A proper man. To be transgender is to perform, right? To roleplay is to perform. Put on a show for one friend, six friends. Plan it out, write it in chunky paragraphs. Just like a child acting out a play for their parents in the kitchen, storytelling is a language that we cannot lose, but many of us do.

I know why I used to roleplay. On the surface, I was seeking a community of people who might possibly understand. Being sewn shut into a body that never quite felt like my own, I could rip those seams apart and start anew. I could be a boy with no judgement, feminine with no question. I didn’t have to ask for permission, nor did I need to get myself on a waiting list for gender-affirming care, because it was there for me at the end of whatever I wanted to write.

I’d stay up so late, and my grades suffered—but I was a million different people. The reality of my world didn’t exist when I was creating, when I was writing. I’m a professional writer now, but I didn’t predict such a reality for myself when I was hiding my phone under the table in science class, responding to a friend’s paragraph about our characters as mermaids, devils, ghosts, whatever we wanted. It was just a way to leave behind the immediate suffering and confusion of my daily world, the strange nature of being a trans child with no allies, no understanding.

Why do I still roleplay? I’m not a teenager anymore. I’m 26, and I live with my partner. We have a lovely home with a goldfish. Maybe just because it’s fun. Why does anyone do anything? Why do people knit or draw or learn the harp? Why do people mend their socks or sing in the shower?

Or maybe it’s because I’m not entirely fulfilled by my body. Maybe, more than anything, it’s because I have been on the waiting list for gender-affirming care for two years now, and all I can do is play in hopes that it’ll push the clock hands a little quicker.

Roleplay is as serious as any of those things for legions of people who dwell on the internet. Micro-networks of storytellers, sharing secret words and crafting special documents. I remember beautifully put-together Google Docs, proficiently designed as if they were for profit. Roleplayers are community managers as well as storytellers. They’re wordsmiths, creatives, designers. Shared through Tumblr, shared through specially made websites, shared through word of mouth.

I have one person I roleplay with now; I don’t seek out others. I have communities in the real world that let me play as much as I want, but I’ve still clawed onto my one little universe. It’s actually quite expansive. In the Discord server I keep with my roleplay partner—who became my best friend in spite of our long-distance—we have around 30 different channels dedicated to vastly different versions of the same two characters. They’re anything but typical portrayals, so far removed from the source material that it’s tough to describe them as homages these days.

We met because we wanted to expand the universe of Edward Teach and Stede Bonnet from Our Flag Means Death. I found them on Tumblr, using the tagging system to find a roleplay partner. I love every universe we have, love all of our words and our unabashed joy. I wish I could print it out, bind it, laminate all of our beautiful words and stick them to every wall in my flat. I love my little world so much. Hiding is impossible, for you are your truest self when you lose yourself inside of a character.

Like cave-paintings, like notes passed from table to table in a busy classroom, many roleplays will be lost to time because they were not made to be permanent. You can often create a downloadable PDF of your work, but I always found that to be a vulnerable and dangerous game. If you delete a Discord server, a group chat, your Kik account, a Facebook page you used to interact ‘in character’ with others, it’s really gone.

But I appreciate my little worlds for what they gave me in every specific moment of my life. Every squishy pain, every deep and mundane sadness, every chance to explore the questions I had about the universe in detail. I still had connection throughout all of my trauma. I could never have asked for much more.

If you liked this article, please help us make more! Become a patron for as little as $1 a month, or make a one-off donation of any amount.

Newt Albiston (they/he) is a writer and cultural critic from the UK. Their writing often covers pop culture, musicology, and gender, and their work has been featured in the Huffington Post, INTOMORE and Oh Reader.

Anna Lark is an illustrator and cartoonist with a background in language education—and a passion for roleplaying games. She has illustrated for Cantrip Candles’ “Feast” series as well as album art for Kinnfolk Music. Her portfolio can be found at annalark.art.